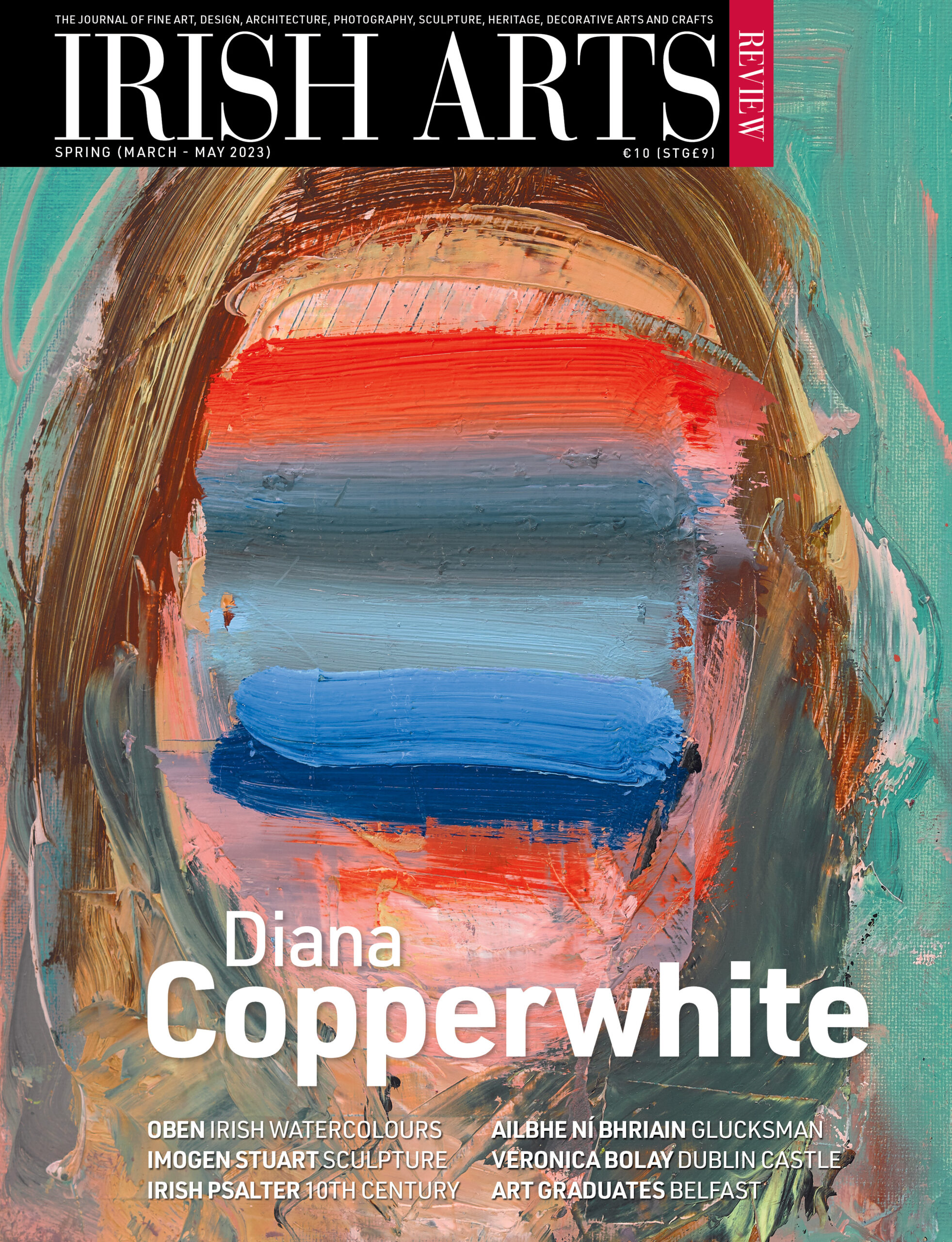

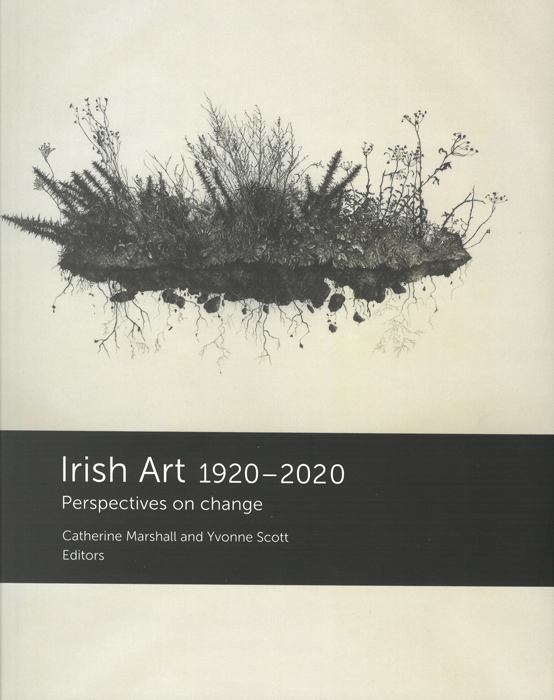

Catherine Marshall & Yvonne Scott (Eds)

Catherine Marshall & Yvonne Scott (Eds)

Royal Irish Academy, 2022

pp 423 fully illustrated p/b

€30 ISBN: 978-1-91147-982-6

Brian Fallon

A great deal of this book may sound opinionated, verbose or even downright coat-tailing. For example, Irish Modernism is taken up by many hands in turn and shaken vigorously in the process. Elsewhere, it feels as if some favourite thesis is being aired – and not always with style or originality. Humour, at times, is in rather short supply: that applies to some (by no means all) of the art on display in the colour plates as much as to the text itself.

What exactly is meant by Irish Modernism? My own generation could at least offer some kind of explanation: it was the art of contemporary Paris joined convincingly to something we could not easily define in words but could see embodied visually in artists such as Nano Reid and Patrick Collins. The work of William Orpen, for instance, was obviously quite sound in itself, but belonged to a world which had become alien to us, like the British Empire – and not for political reasons alone. Ireland, in fact, after the long, drab centuries, had begun to rediscover itself visually, and high time it was too. After all, the Literary Revival had set an example.

it appears, we now have a kind of déraciné art which prides itself on its lack of ‘roots’ – a dangerous boast, because art, like it or not, is an intrinsic part of the daily world

However, there was more to it than that. There was also America, which few of us had regarded as being one of the Great Powers when it came to visual art. The new American painting was, to a large extent, abstract, but somehow that was part of its power. Fairly soon the Living Art exhibitions were ablaze with home-produced abstract paintings – often mediocre, as it happened. But the wheel kept rolling; abstraction became old hat quickly enough in the end, and soon events such as Conceptualism were being touted everywhere, though, with a few exceptions apart, they seemed short of invention. And finally, it appears, we now have a kind of déraciné art which prides itself on its lack of ‘roots’ – a dangerous boast, because art, like it or not, is an intrinsic part of the daily world in which we work and breathe.

The colour reproductions in this edition maintain a good level throughout. This is a biggish book, quite heavy to lift or handle, but it is encased only in a light cardboard binding. A sturdier cover is surely called for.

There is no mention of the late Stephen McKenna, not only a fine painter in his own right but also a man who did much to bring the Royal Hibernian Academy into serious reckoning again. Imogen Stuart – a gifted and prolific sculptor, whatever the pseuds may think – is allowed a single mention, while Melanie le Brocquy, Conor Fallon and Carolyn Mulholland don’t feature even once. The critic Brian O’Doherty, in his long sojourn in America, wrote books on art and artists that earned him a deserved reputation; but his quasi-resurrection – or whatever you chose to call it – as ‘Patrick Ireland’ became boring and twee as the years passed. If his friends chose to remember him – as well they might – surely he deserves something better than his representation here.

Several of the articles in this commodious but uneven book seem to me more than a little jejune and self-admiring. By contrast, both

Catherine Marshall and Yvonne Scott make solid, well-considered contributions, as you might expect from them. However, in my opinion, the most satisfying piece of prose (and scholarship) is the late Nicola Gordon Bowe’s essay ‘The Arts and Crafts Movement and Its Influence on Irish Art’.

Brian Fallon is art critic.