David Caron reviews Neil Shawcross’ work in stained glass, the majority of which was created for churches in Northern Ireland

Neil Shawcross has enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a painter of, among other subjects, portraits, nudes and still lives. His reputation was consolidated by his election as an academician of both the Royal Ulster Academy and the Royal Hibernian Academy, followed by an honorary doctorate from Queen’s University Belfast and an OBE in recognition of his services to the arts in Northern Ireland. To mark his eightieth birthday in 2020, Riann Coulter reflected on his celebrated painting career in the Irish Arts Review (vol. 37 no. 1). What is less well known is that, in parallel with a prodigious output of works on canvas and paper, Shawcross also designed many stained-glass windows, between the early 1960s and the late 1990s, for over twenty locations across Ulster.

Shawcross began creating works in stained glass not long after relocating from his native Lancashire to Belfast in his early twenties, when he took up a position as a part-time lecturer in the city’s college of art in 1962. He got to know the Fine Art students who were working with traditional mouth-blown streaky glass and was ‘fascinated by the ribbons of colour within the [sheets of] glass, kind of beautifully free flowing’. Recognising the natural potential of this type of glass (known as ‘antique glass’ or ‘pot-metal glass’), Shawcross began his own experiments with cullets (offcuts), arranging them on sheets of clear plate glass. They were fixed in place with epoxy resin and the gaps were then filled with a tar-like substance.

To read this article in full, subscribe or buy this edition of the Irish Arts Review

From 1960, when a chance meeting with Cecil King led to his work being included in a show at the Ritchie Hendriks Gallery, Dublin, Michael Kane was a formidable, indomitable presence in Irish cultural life.

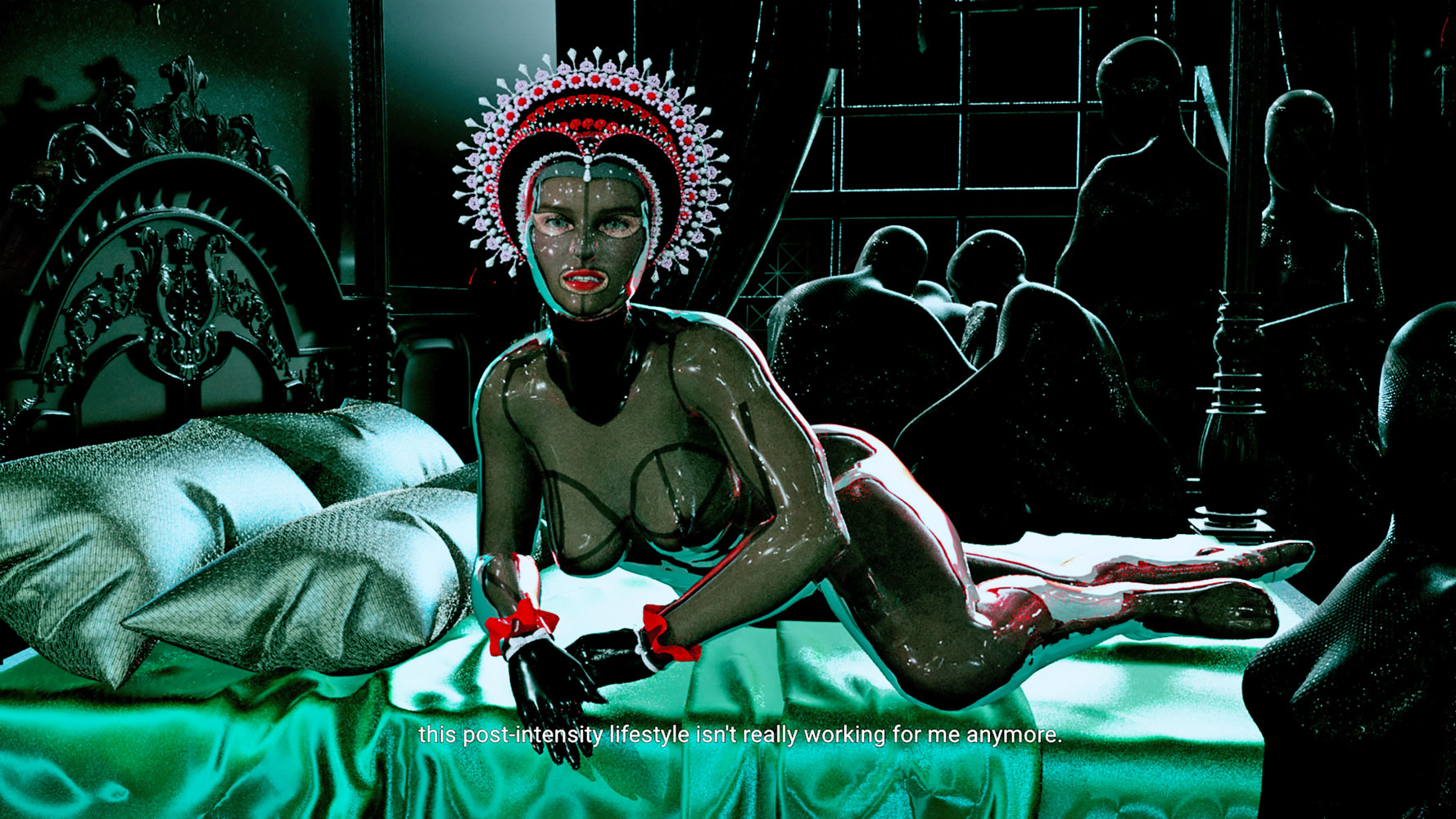

Emer McGarry considers the work of Marianne Keating, which brings to light overlooked stories of Irish migration, labour and resistance

The exhibition treats the archive as a tool for building new futures, writes Seán Kissane