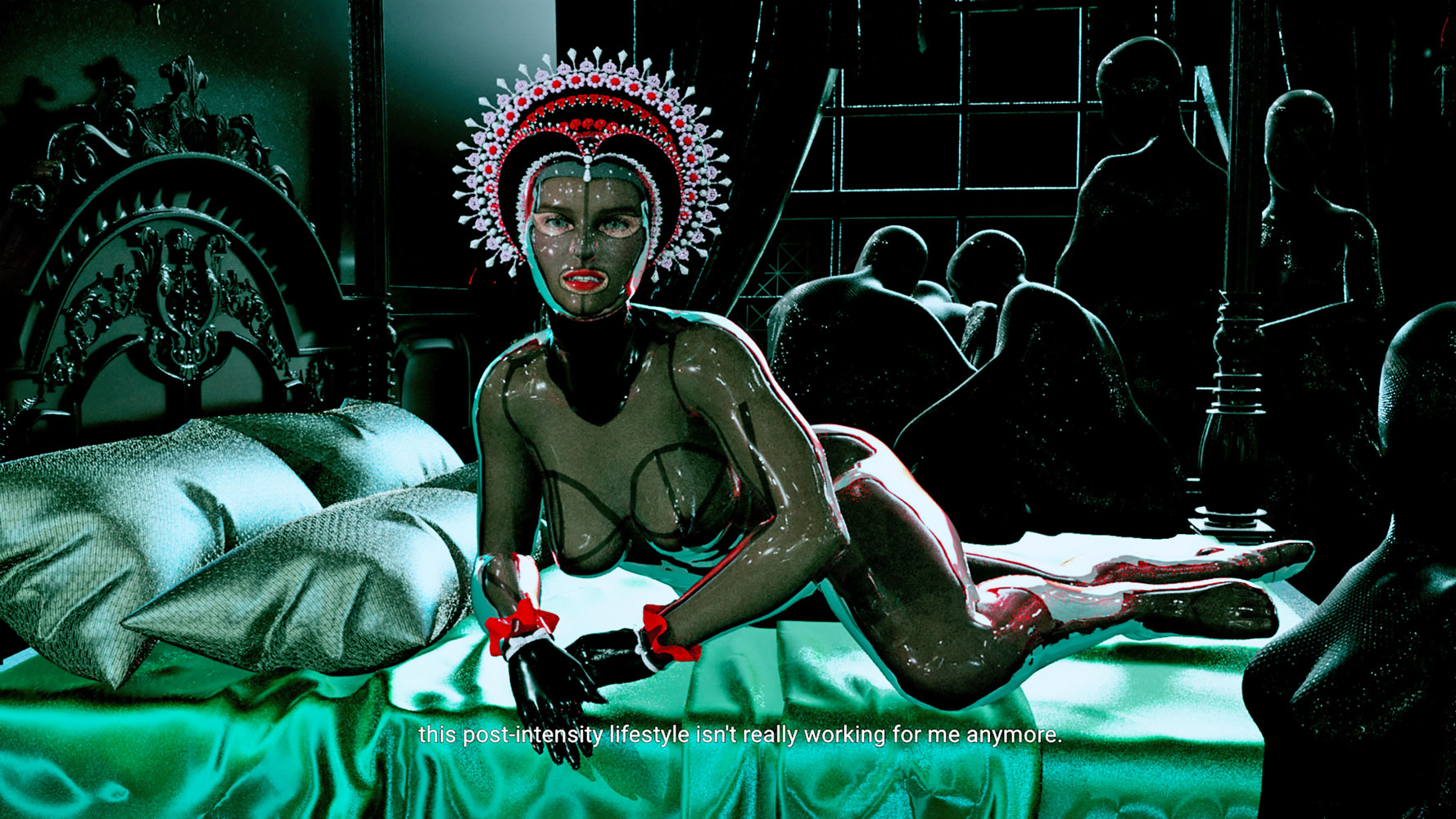

Philip McEvansoneya considers a painting of an Irish subject by the English artist Walter Sickert

A young man is seated by a window facing the viewer. To the right, a mature woman is seen in profile as she looks down on him, holding the back of his chair in an inquisitorial way, as if calling him to account. He cuts a diminutive figure next to her substantial form – an iteration, perhaps, of the conventional comedy of the termagant and the hen-pecked male. But the moment of the encounter is freighted with another kind of tension because in the foreground, prominently propped against an improvised rest, the drawer of a table, is an elongated rifle. The weapon introduces a jarring note into an ostensibly domestic scene.

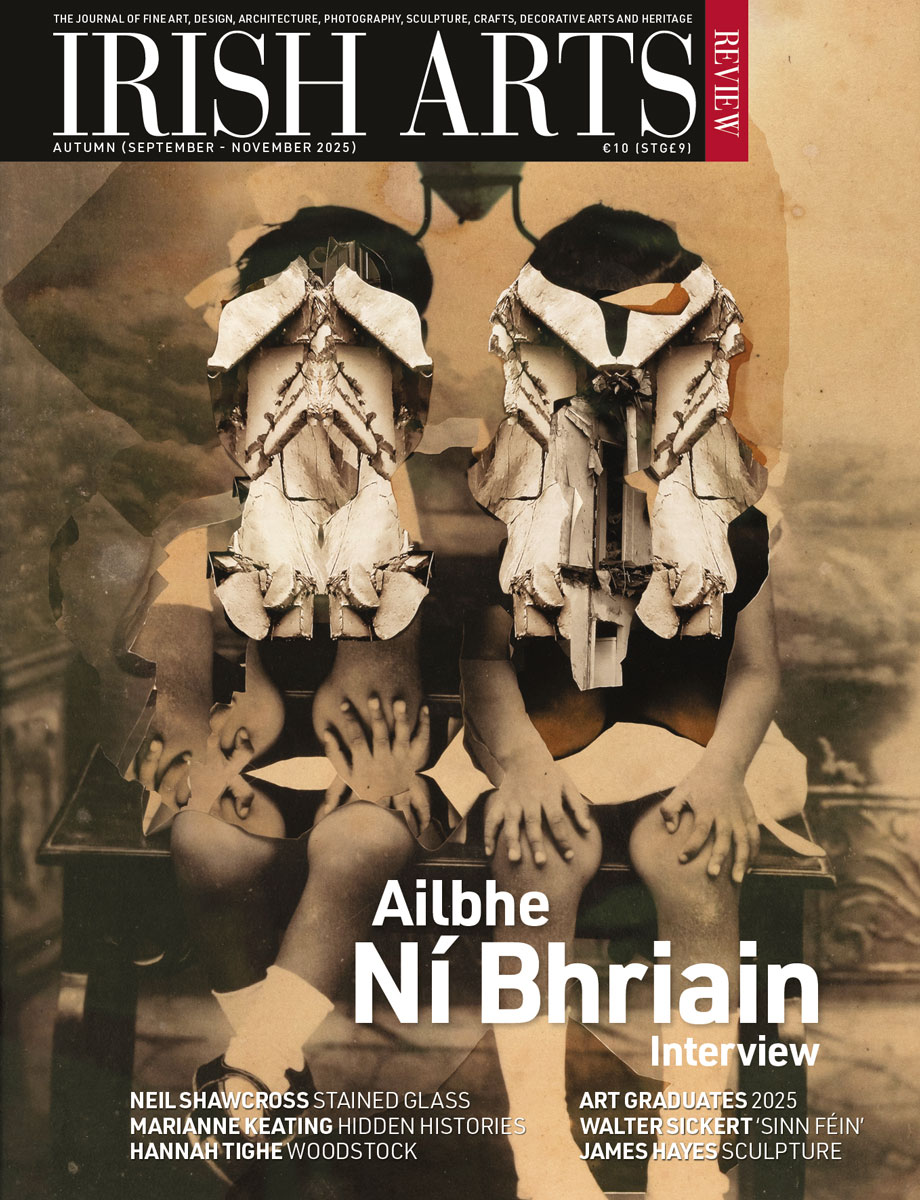

Sinn Féin (also known as The Sinn Féiners) is a little-known work by Walter Sickert, the English artist of Danish-German-Irish origins, the Irish part being through his grandmother, Eleanor Henry. Sickert had a prolific and high-profile career in both painting and printmaking, depicting subjects he found in London as well as others derived from his travels in Belgium, France and Italy. His Irish-related scenes are few. In England, he is best known for his portraits and genre scenes, including a number of moody and mysterious interiors with figures and music hall subjects. Among the genre scenes is Tipperary (1914, private collection), which shows a woman playing the piano, watched by a soldier in khaki uniform, presumably singing the popular wartime song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’. In fact, there are two paintings with this title, with different compositions, the second (1914, Tate Britain) lacking the soldier.

To read this article in full, subscribe or buy this edition of the Irish Arts Review

From 1960, when a chance meeting with Cecil King led to his work being included in a show at the Ritchie Hendriks Gallery, Dublin, Michael Kane was a formidable, indomitable presence in Irish cultural life.

Emer McGarry considers the work of Marianne Keating, which brings to light overlooked stories of Irish migration, labour and resistance

The exhibition treats the archive as a tool for building new futures, writes Seán Kissane