Carissa Farrell visits the studio of sculptor Catherine Greene where the magic of transforming abstract idea into plastic form takes place.

There is a vigour in the sculptural practice of Catherine Greene that contradicts common assumptions about figurative sculpture. It is a hardy resistance to monumentalism. For Greene this resistance functions like a compass, guiding her through her intuition towards strategic modesty that foregrounds the integrity of the art obect and audience against the artist’s ego. As Greene says herself, ‘it becomes egotistical to say that I will make an iconic work…’ But an artist can only sustain such a measured approach by having a core vision that anchors it. Vision is the Holy Grail for an artist, it is felt and very much part of an artist’s personality – it is in the kernel of an idea and a sense that an outcome is possible, it is about making and unmaking, it is about failure as much as it is about success. I spent some time with Greene in her studio where she described her ideas as though they exist around her like an aura – they are hers and deeply felt but she must search for them as though they are intimate possessions that have been temporarily mislaid. But as with all artists the moment arrives where she can pull them into herself, transform them and make that leap to innovation, the final emergence, the forming, shaping and imagining which is very much under her conscious domain.

Greene’s back catalogue is allegorically figurative, rather than representative. Borrowing from straightforward realism and an impish instinct for surrealism she creates three-dimensional forms that draw on a mix of the ordinariness of everyday life embellished with dreamlike diversions from her psyche. She maintains a balance of these real and imagined worlds in both her public and private commissions and gallery work. It is perhaps best illustrated in her memorial to Thomas Francis Meagher in Waterford City (Fig. 6). It is the kind of commission that demands a traditional and monumental approach – a military figure on a horse wielding a sword – such was the specificity of the brief. Yet Greene produced an aspirational rather than triumphalist work, infused with stillness, dignity and humility – as though Meagher is still caught in a dream that has yet to materialize. Compared to the heroic and theatrical monument by Charles J. Mulligan at the Montana State Capitol Building where Meagher was Acting Governor, Greene’s work offers insight into the man rather than the legend.

Even though a large proportion of Green’s oeuvre has been produced in the most permanent of materials that is bronze, there is a perceptible threat of instability running through them. They are flighty and capricious. Greene brings buoyancy to almost everything she makes, whether strategic or not, as though the work could break free and abscond from her in spite of its weight and rigidity. It introduces a vulnerability that ultimately, as she states quite democratically herself, ‘will be judged by people’. In a business where stylistic trends are taken up by artists gifted with a technical adroitness that drains the life and soul out of their work and the audience, it is a privilege to see the living evidence of the uncertainty that complicates an artworks’ production. Perhaps the best examples of this are Greene’s very fine smaller bronze works, such as Terra Incognito, Icarus’ First Trail, Planetary Map, and Tobias and Sarah. A particular favourite of mine is The Cartographers in which two Renaissance men stand of the armature of a glove, one whispers in the ear of the other who leans forward, head down with concentration. The speakers’ coat flaps in a breeze as they casually teeter on top of God’s earth. These men are dreamers and innovators whose vision literally shrinks the vastness of the work under their feet (Fig. 3).

Allegory is an important ingredient in Greene’s conceptual process. Some works appear representative of certain individuals but are really metaphors for other meanings that nod respectfully to the conventions of historical and allegorical art. In 2003 Greene was commissioned to make a work in memory of Dermot Morgan (Fig. 5). Choosing to make a non-figurative work was a fitting memorial to a man whose guise was inextricably entwined with his television alter egos, Father Ted and Father Trendy. Morgan would have been pleased, after his untimely death at forty-six, his collaborator spoke of his long wish to be recognized as a writer and artist rather than the larger-than-life characters that he was associated with.

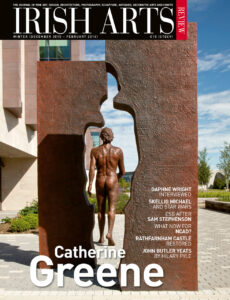

The figure has a self-conscious aura of classical sculpture updated by a casual independence that fits with the experience of third-level education

The work takes the form of a bronze throne and, if we could imagine a seat in an ancient Celtic royal household this could be it. Titled Jester’s/Joker’s Throne it references Morgan’s role as a satirist, or as Greene describes, ‘The very clever fool who is pitted against convention and brave enough to see the truth.’ The frame below the seat is inset with an all-seeing eye, bringing to mind the strength of Morgan’s work and how the Irish political establishment couldn’t stomach the fearlessness of his biting satire. On a lighter note the overall scale is slightly larger than life, creating infinite photo-opportunities for visitors to Merrion Square. There is a sense that if you sit in it, the joke might still be on you, as though Morgan’s spirit is somewhere nearby chuckling quietly. In keeping the Greene’s instincts it is set into a modest cobbled bay and is utterly lacking in spectacle.

When Greene was tasked with an extremely demanding commission to make a large-scale crucifixion work for the new Basilica da Santissima Trindade at Fatima, Portugal, she felt compelled to avoid the melodrama and tragedy that heretofore dominated the genre (Fig. 1). The Basilica is a marvel of contemporary architecture, designed on a grand scale with a colossal interior that seats 9,000 congregates. Greene preferred to depict Christ as the redeemer no longer suffering, a choice that is more fitting within the optimistic grandeur of the location. Rather than hanging painfully on broken arms, Christ appears upright with arms and hands outstretched wide in anticipation of Resurrection. Greene’s stylistic approach is close to the manuscript depictions of Christ form the early Middle Ages when symbolism had not yet been superseded by sublime mimesis. The crucifix lacks the menace of solid form, being made of two bars that simply approximate the shape of the cross. Christ’s body is tensed with vigour and strength and lifted upwards with the possibility of flight. It is a redemptive work that sits well in its very impressive surroundings.

Greene’s most recent commission for the Sutherland School of Law at UCD, Portal comprises the figure of a young man walking out of a mould which has been broken in two halves and placed a short distance apart (Fig. 8). It is hard to respond to this work without imagining it being in motion. The figure has a self-conscious aura of classical sculpture updated by a casual independence that fits with the experience of third-level education. Greene had described how Rodin could animate the space around a work by creating a ‘tension in the void as much as the material’. In negotiating its path into the lectures at the Law School each morning, it is easy to imagine saying ‘excuse me’ as you pass around or through it. In this way Portal is designed as an intervention into the busy territory of student life, acting as a daily reminder that the experience of university is a journey elsewhere, rather than en end in itself.

Greene is currently working towards a solo project at the Irish Georgian Society’s Assembly Rooms in October 2016 for which she is returning to her roots in otherworldliness. Comprising a series of more melancholic works, she describes them as an exploration of ‘…the line between the human and the animal soul’. One work Wolf and Men, is part of this series of centaur/satyr-like human/wolf figures that stand perfectly still, hands clasped at their sides with heads sorrowfully stretched upwards to the sky (Fig. 4). Still very much at the incubation stage, Greene is excited with this new departure and indeed the opportunity to concentrate on her own personal brief rather than the restrictive confines of commission work. Having consolidated her practice in recent years wit a well-equipped spacious studio and time to work in it, and with a lead-in time that is just generous enough to allow for development without losing freshness, this show promises to be an interesting one.

Photography by John Searle. All images ©The Artist.

Carissa Farrell is a curator and arts manager living in Dublin.