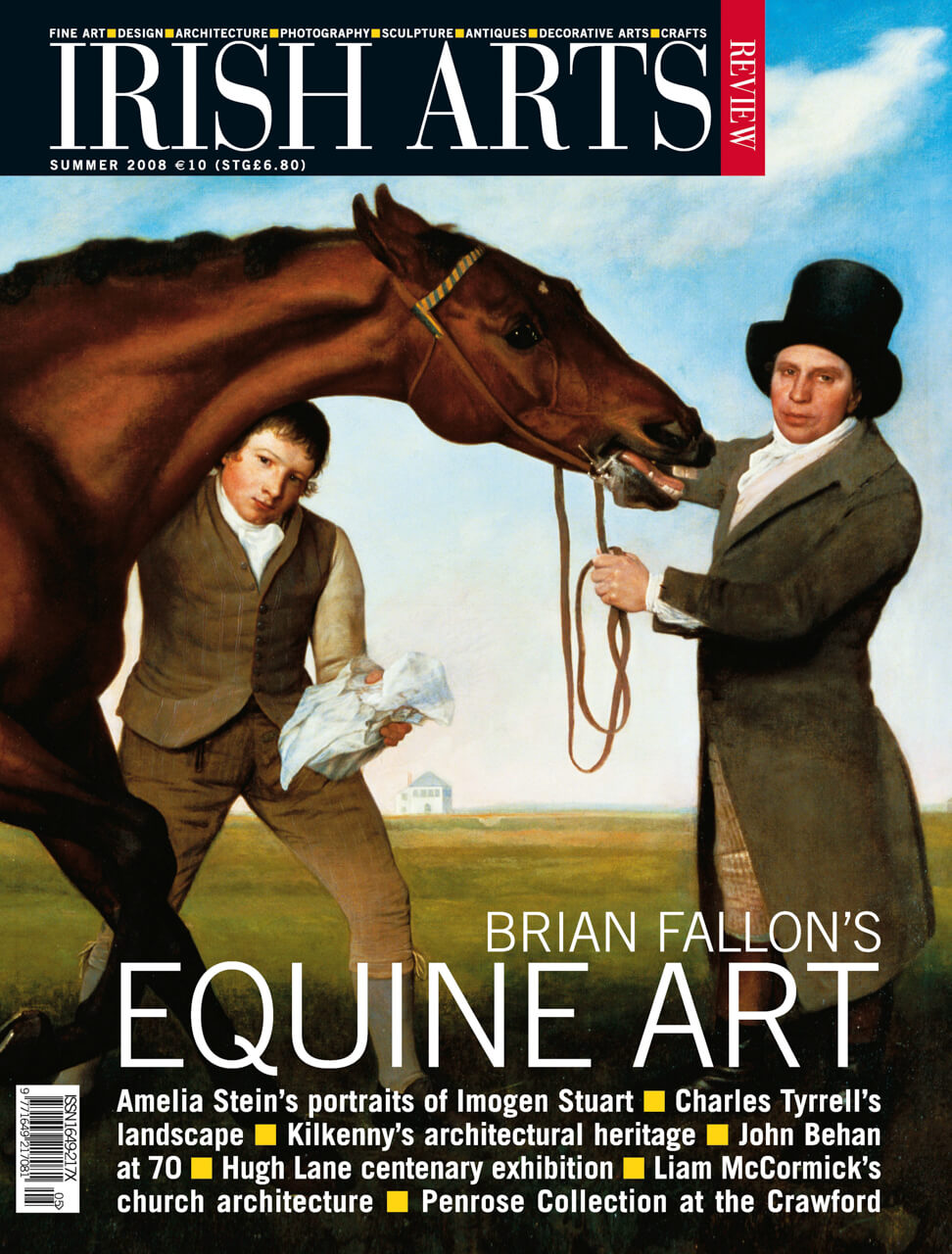

To celebrate Imogen Stuart’s election to Saoi, we re-publish here Amelia Stein’s eloquent series of photographs documenting Imogen in the creation of an Angel of Peace, for St. Teresa’s Church in Johnson’s Court, Dublin, from the Irish Arts Review Summer 2008 edition.

Stephanie McBride views the plan and process of an angel’s journey in Amelia Stein’s studies of Imogen Stuart’s studio.

Unlike Leopold Bloom’s Grafton Street of June 1904, ‘gay with housed awnings [which] lured his senses’, this spring morning the street is grey, thronged with shoppers and curious tourists who are unaware that high above the sea of commerce is an Angel of Peace, watching over all from the bell tower of St Teresa’s Church in Johnson’s Court. Created by Imogen Stuart, the angel was unveiled on World Peace Day, 1 January 2008.

The angel was first proposed over a decade ago. Imogen Stuart explains that the initial site was inappropriate but the idea remained and was eventually renewed when the Prior of the church envisaged it on the tower, and viewing the tower from Grafton Street, Stuart was convinced of its suitability as a setting for the angel. Planning permission was sought and a surveyor was required whom she herself sourced. At one point, a seven-foot plywood version of the angel was temporarily attached to the tower as Stuart moved through the various stages of the process from drawings, armature and plaster to the final, finished bronze figure that now permanently looks down from the tower.

Entering Imogen Stuart’s studio, she remarks that it needs a sweep. Apart from a small patch of pale blue polystyrene dust particles at the foot of a bench, the space is neat, ordered and serene. ‘I need to have order to begin new work,’ she explains. A Surrounded by maquettes and various versions of her works, she indicates the head of Brian Fallon awaiting completion which she started before the Angel. I notice the ‘green ladders’ stowed against one of the walls. The roof ladder is clad in lead and inscribed with the Litany of Daniel, the decorator’s ladder is made of Indian paper bearing the words of a psalm, and the wooden builder’s ladder has St Patrick’s Breastplate inscribed on its steps. Stuart’s collection of ladders invoke the sacred as well as the natural life of beasts and birds. On another table is her cast iron Tree of all Seasons – which she envisages as a large, revolving piece to enact the cyclical movements. Pinned to the walls are notes, honorary awards, mementoes and drawings – the room is both a workshop, study and contemplation space. Imogen talks about the problems of working with heavy materials, of how plaster is difficult too, and of trying to carve some thing with a hatchet. It suggests an exquisite paradox, this image of the delicate art of carving blown apart by a crude hatchet, as the Angel of Peace is brought to life.

Artist Amelia Stein has documented the process in a series of portraits of the artist in her studio. Stein’s response to her subjects is fluently engaged. Her series of artists’ portraits demonstrates her finely-tuned practice – in one, the artist’s face caught in a quiet moment, in another, a metonymic representation giving us a powerful image of Olwen Fouere’s hands in one intense clasp. In ‘Loss and Memory’, a series of photographs of her deceased parents’ belongings are charged with an emotional intensity and grace that avoids any sentimentality.

Stein’s portraiture shows an eloquent and assured probing of the genre’s possibilities, and in this set of photographs of Stuart, her responsive and intuitive approach to the creative possibilities of the project, her deft use of black and white and her accomplished use of natural light are clear. Aware of the significance and value of work-in-progress, and the often paradoxical momentum towards completion and installation, her camera/eye captures those moments of quiet thought, action and decision – allowing us to enter this liminal space of creation.

In the beginning there is nothing (Figs 2&3). Or not quite: the genesis of an idea, without form or substance yet, then floating in a white void. A shaft of light links the outstretched hands of the sketch with the plaster angel (Fig 5), now gaining shape and definition, revealing an intermediate stage before the eventual bronze casting. Still lives are here charged with light’s energy. There is a hint of alchemy and magic in this process, which turns light into liquid then to plaster and finally bronze.

The artist on a pedestal, caught between the plan and process and solid artwork – the Angel of Peace, chained to the studio wall for ease of working (Fig 4). These chains could be strands and sinews from a Victorian factory or dockside, or a medieval torture chamber, or the pulleys from a stage backdrop. In this image her work-in-progress is made fully visible. Through the window a natural spotlight, illuminating the angel’s form taking shape under her hands – her shadow fused with her creation. Stein’s composition offers two images of the angel – presenting a kind of alter ego, looking on as his more robust identity acquires form and sub stance – her photograph making explicit the stages in this birth. What is it about artists’ and writers’ rooms that intrigues us? From the acetate-spattered floor of Antony Gormley’s studio to Michael Craig-Martin’s neatly-stored containers of acrylic paint on his work bench, images of these rooms entice and invite us, as sacred locales, at the heart of the creative idea and act. In their historical survey of the term studio and its variations (bottega, studietto, studiolo), Cole and Pardo indicate the multiple uses of the artist’s studio, and the often contradictory impulses within its confines; a private reflective space, yet a place of frenetic activity too. Portraits of artists in their studios have a long history – they even have their own genre ‘schilder kamer’ offering diverse approaches and variations on the theme, from St Luke painting the Virgin to Rembrandt’s Artist in His Studio in which the artist is subordinate to the centrality of the painting, to the meticulous reconstruction in the Hugh Lane Gallery of No. 7 Reece Mews, London – where Francis Bacon felt ‘at home here in this chaos because chaos suggests images to me. And in any case I just love living in chaos’. (2) The currency of the artist’s studio as the site of creation is again shown in Brancusi’s reconstructed studio at the Pompidou Centre, Paris and in the many photographs and commentaries on Giacometti’s studio – which according to one visitor was ‘thick with cigarette smoke and plaster dust, forested with his elongated figures and emaciated busts, the walls obliterated by tracings and retracings of figure studies… the light that streams in is grey and dull’.(3) The drive to record the creative process reaches a further fetishistic intensity in film, exemplified in the attempt to capture Jackson Pollock at the moment of creation; the artist forced to simulate his technique on a sheet of glass mounted above the camera lens.(4) Perhaps the very stillness of the still image is what makes it so appropriate to capture the relationship between artist and studio. The moving image, with its rhythm and momentum, tends to evacuate the more reflective mode of address of the photographic portrait. In her images recording this unique narrative of genesis, Stein’s art makes the journey exnihilo manifest, casting light into the site of its creation and creator prior to its emergence onto the public stage.

Stephanie McBride is the author of Ireland into Film: Felicia’s Journey (2007).

Photography Amelia Stein.

1 Inventions of the Studio, Renaissance to Romanticism, Michael Cole and Mary Pardo (eds), University of North Carolina Press, 2005

2 www.hughlane.ie/fb_studio

3 ‘Laboratory for Likenesses: Giacometti’s Studio’, Frances Morris in Alberto Giacometti The Artist’s Studio, Tate Gallery, London, 1991

4 Jackson Pollock, Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg, 1951

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 25, No 2, 2008