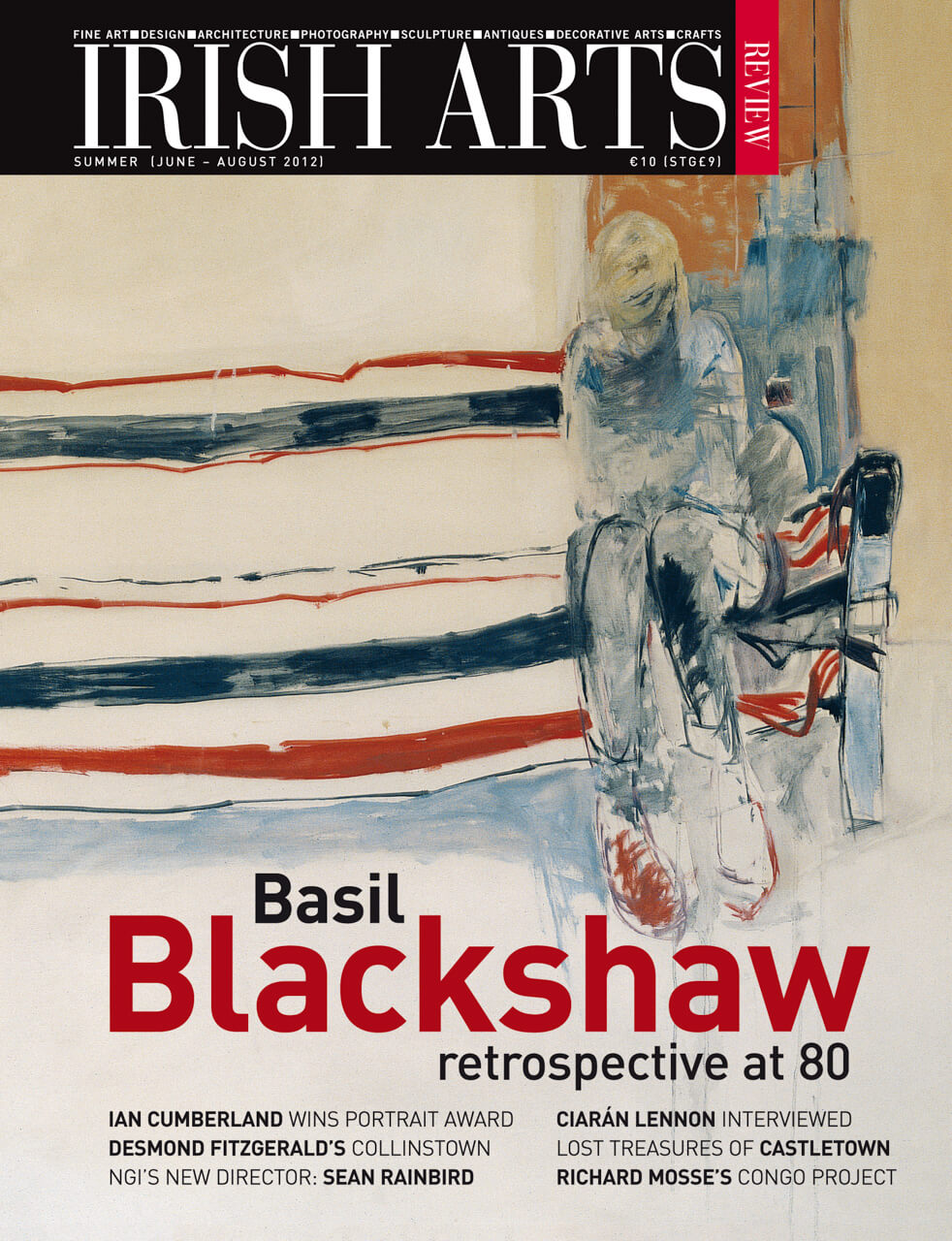

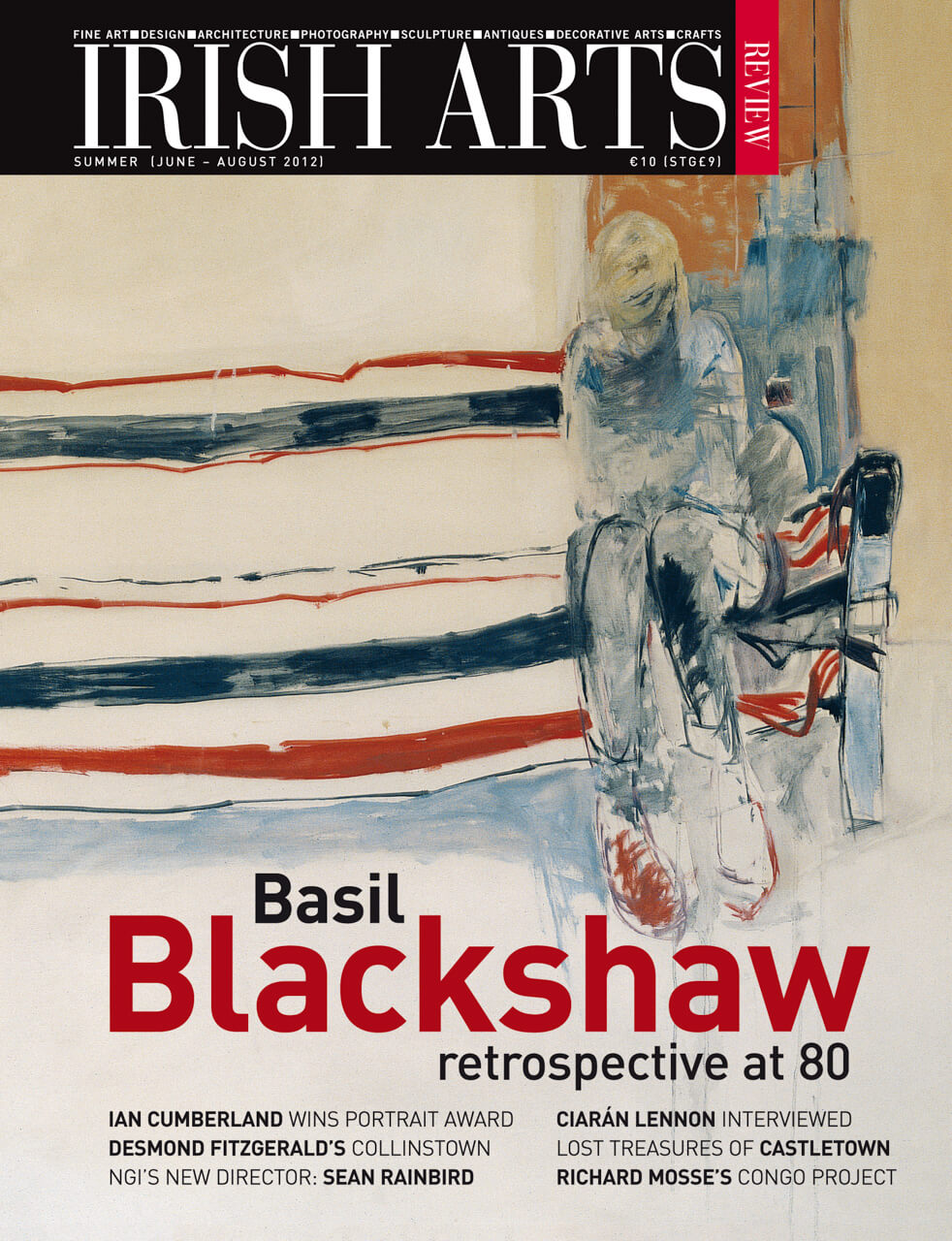

From a rural setting in County Antrim, Basil Blackshaw has contributed a new chapter to the story of Irish art, writes Brian Fallon as the retrospective at the F E McWilliam Gallery marking Blackshaw’s 80th birthday continues.

With a career stretching back over roughly six decades, Basil Blackshaw could justly claim to have added an entire dimension, or at the very least an extra chapter, to Irish painting. Even this statement seems limiting in itself, since Blackshaw in my opinion is an artist of European size whom the Venice Biennale, or some other prestige exhibition, should by now have honoured as a living master. This is not likely to happen, however, nor will any special notice be taken in London (or Manchester or Glasgow, for that matter) of the fact that a major painter, who is also a UK citizen, has reached the age of eighty.

What is vaguely called ‘international fame’ is not necessarily of much value to an artist, except possibly on a financial level. To my knowledge, Blackshaw has never coveted it; in fact, rather the reverse, since he is a painter who values his privacy. Without being either a hermit or a misanthrope, he has kept a certain, safe distance from the public arena and has concentrated on producing his work, not on promoting it. Though he does not lack recognition, it is within a rather limited context; if you ask some well-known London critic (as I have done more than once) for his estimation of Blackshaw’s work, you are likely to be answered with a shrug of blank puzzlement or even an incurious stare. And I doubt very much if this situation is going to change greatly in the near future.

In retrospect, his long stint as an artist has been less a success story than an epic of survival. For an Irish painter this is not exceptional, if you recall Tony O’Malley’s years of virtual anonymity before the Irish public discovered him when on the verge of old age, or Paddy Collins’ uphill battle to keep his place in the sun. Nano Reid, a major artist, led a life of semi-obscurity in Drogheda; Mary Swanzy, painting away almost unnoticed in a London suburb, faded out of public view for decades. However, Blackshaw has also had to cope with a broken marriage, a slide into alcoholism, and – to cap it all – a destructive studio fire which occurred just when he was moving into a radically new phase as a painter. He also has known the frustration of being out of favour or fashion for quite lengthy periods, after a spectacular start which saw the Ulster Museum (mainly through the initiative of the late John Hewitt) acquire a landscape painting by him when he was not much past twenty. The Gods have rarely been on his side, or so it seems.

Yet what marks him out particularly is that after a career involving several changes of style, and even certain fallow years in which he did not seem to be heading in any real direction, he has achieved a kind of ‘third period’ of outstanding creativity. Very few Irish painters have done that, with the obvious exception of Jack Yeats who remains a figure sui generis. In spite of Blackshaw’s famous precocity as an artist, his early phase was largely spent in a milieu not at all calculated to favour boldness or originality in a young painter. He still speaks warmly of his tutor, the elder painter Romeo Toogood, who generally gave him his head and, when Blackshaw (in his own words) was trying to paint rather like Kokoschka, would restrict himself to quiet comments such as ‘think about the edges sometimes.’ Yet the plain truth is that Belfast, though probably offering a better training for young artists than the almost moribund NCAD in Dublin, remained a provincial British city in many or most respects. And English art training at that time, like the bulk of English artists, was going through a relatively timid and conservative phase.

In spite of the major achievements of Nicholson, Hepworth and Hitchens, the people who won reputations in the 1950s were quite minor by the standards of Paris or New York – men such as Graham Sutherland (then treated almost as a god), John Minton, Keith Vaughan, Alan Reynolds et hoc genus omne. The abstract school of St Ives had not yet gained any wide degree of recognition, while Francis Bacon was still relatively little known outside the pubs and cafes of Soho. In spite of a high degree of Frenchification in all the arts, both art education and public taste encouraged a low-keyed or inhibited colour sense, conventionally correct drawing, and an all-too-predictable range of subject matter. Blackshaw inherited a localized version of this in Northern Ireland, and undoubtedly it affected or even inhibited his natural development. He remained, of course, too much a born painter ever to be untrue to himself, but while his temperamental inclinations were towards a kind of Expressionism (as his very early work shows), his immediate milieu pointed him in the opposite direction. And when abstract art began to call the tune, as it did particularly loudly after the American conquest which began in the later 1950s, he must have felt even more isolated. Abstraction has never been his thing, though he has been marginally affected by it. Then came the 1960s and Pop Art, but this signalled the advent of a smart, streetwise, basically metropolitan style while Blackshaw always remained, at heart, a bona-fide countryman. Apart from his student years in Belfast, he has never lived for more than short periods in any city, big or small, and today rarely moves out of his studio-home in rural Antrim. His early familiarity with animals – his father trained horses – and his love of country life and habits, have been two of the decisive elements in forming his creative psyche.I Even before he thought of becoming a painter, he had painted and drawn animals; as he himself has said, he never produced child art, just ‘bad grown-up pictures’. Another key element which increasingly put him at odds with himself, and caused a dichotomy which it took years to resolve, was his natural gifts as a draughtsman. I think it is more or less stating the obvious to say that no Irish artist of his generation – with the possible exception of Patrick Graham, who is a little younger – has been so innately talented in this area, and his early training intensified it. But Blackshaw was an equally born handler of paint (rare gift), and the twin tendencies often tended to pull him in different directions. He found some kind of solution through studying Cézanne, a painter in whom he has always seen a strong Expressionist element in spite of his reputation as a classicist. (I fully agree with him on this, by the way.) Cézanne’s example helped him to organize his landscape pictures better, and I would say was also an influence in his handling of still-life themes, or even on some of his figure paintings. Above all, however, the Master of Aix seems (posthumously) to have helped him to avoid becoming what painters call ‘tight’ and to tap more into his own inborn painterliness, which had been sporadically at war with a basically academic, linear training. The two men were not fellow-spirits, nor was Mediterranean classicism part of Blackshaw’s emotional or intellectual inheritance; but the debt is undoubted. One painting, dating from as late as 1970, is actually entitled Cézanne Landscape and some years before that Blackshaw had painted Cézanne’s Gardener a kind of personal homage based on the familiar, sun-soaked picture of the rustic gardener Vallier. Taken all round, Blackshaw’s early work would entitle him, on its merits, to a secure place in Irish (or English) art but would not make him a major figure. It is vigorous, individual, and well-made, at times genuinely lyrical, but overall it does not conquer new ground, nor is it particularly adventurous in terms of colour. The ensuing period, though it produced its quota of fine works and even a number of masterpieces, is by contrast rather uneasy and subject to strong cross-currents; in the end, you feel that the artist too often is searching rather than finding. (It was, of course, a difficult period in his private life – especially concerning his marriage to the Australian artist Anna Ritchie. There is no overall sense of direction and little consistency of style; full ease and maturity, somehow, have not yet been reached. Admittedly, Blackshaw is not an artist who has ever ‘developed’ in any linear, ‘progressive’ sense; instead, he has moved from one style or phase to another seemingly as the mood took him. Or in his own words, ‘you never know what you’re going to do next.’ For him, painting is more a voyage of discovery than an inexorable progression towards a fixed point.

One common merit which the middle-period and later work do possess in common, however, is an exceptional versatility; none of his contemporaries, it is quite safe to say, can command an equal range of subject matter or theme. As a painter of horses he is probably the finest since Jack Yeats, and as a painter of dogs (Fig 5) he is rivalled among his contemporaries only by Craigie Aitchison; as a portraitist he is as good as just about anybody of the last eighty years, either here or in Britain;4 as a landscapist he is variable and uneven but, at his best, inspired and almost visionary; and as a painter of occasional still-life and flowerpieces, wayward yet sometimes quite magical.

In the 1970s Blackshaw began to take notable forward leaps in his use of colour and by certain of the many racehorse pictures he produced about this time, which are quite daringly free in style and brushwork. (Others, by contrast, are relatively conventional and look rather like bread-and-butter jobs as, presumably, they were.) A major tour de force of sheer technical virtuosity was achieved in the massive (182x365cm) picture entitled Grand National (Foinavon’s Year) of 1977, commemorating the famous race in which most of the competing horses fell along the way and allowed Foinavon, a rank outsider, to finish almost alone. It is not a striking work in terms of colour, indeed it is almost an ‘academic’ picture, but the grasp of form and construction it displays would show up most traditionalist painters as semi-amateurs.

It was in the 1980s, however, that the painter in him was virtually reborn and the draughtsman, so to speak, kept firmly in his place. Times were changing, of course – the New Expressionism was raging in Europe, and in Germany in particular; the great Expressionists, such as Beckmann and Dix, were being rediscovered; Bonnard – long written off as a belated Impressionist – had became hugely influential; Balthus was increasingly regarded as the greatest living master. The Duchamp cult of the 1960s and 1970s died a death, and while Conceptualism continued to be the style officially favoured by many of the museums, it had never really gripped the public. Joseph Beuys, the guru of his generation, was already a falling god. Painting, in short, was back in favour, if indeed it had ever really lapsed from it. Perhaps Blackshaw gained fresh impetus from all this; or in his own work everything was coming together at last, after his growing awareness of facing an inner crisis; perhaps he was now prepared to take the big risks and allow his innate exuberance, puckish humour and powers of invention full play. Above all, his colour sense was virtually transformed and became extraordinarily rich, fecund and luminous, while the brushwork took on a life of its own. All this did not, of course, take place overnight, but the fact remains that inside a surprisingly short interval of time, a highly gifted artist more or less re-created himself into a major one.

One form this took was a new interest in the nude, which had never up till then been one of Blackshaw’s main preoccupations. There was an element of collaboration in this, since Jude Stephens, his new model (Fig 12), was a strong personality in her own right and no mere foil to the sometimes impish, mischievous painter. (She is now married to the highly talented Graham Gingles.5) The paintings and drawings he executed of her, including what a photographer would call ‘head shots’ as well as half-length and full-length nudes, are already becoming part of Ireland’s folk-mythology of art; in format they are quite often on a large or even monumental scale, virtually denuded of backgrounds or ‘props’, and with little attempt at traditional modelling. The human figure, the human presence, is left to dominate the surrounding space alone, which almost unfailingly it does. His landscapes, too, became powerful and simplified, throwing most topographical references out the studio window and allowing elemental shapes and colours to speak for themselves. Even the animals and birds Blackshaw painted were transformed into something heraldic and almost mythic; a cock pheasant acquires a kind of symbolic aura, a dog becomes something more than a dog while retaining its canine identity; and in the picture entitled Dolly (Fig 6), what in real life was probably a quite ordinary nag is painted a glowing red and takes on a quasi-mythic status. (Blackshaw has told the critic Brian McAvera that he admires Franz Marc, whose blue horses became a potent symbol of Expressionism at its most visionary.)

This was not the sum-total of his new activities, however. As I have written elsewhere: ‘There is also a large and very special category that stands outside all these and is entirely sui generis. It might roughly be defined as the special ‚ÄúBlackshaw subject,‚Äù meaning (very broadly) something quirky, unpredictable, occasionally ultra-personal or private, often based on sights that are familiar and everyday, or on quite nondescript things that just happen to have caught his eye or his fancy and are re-shaped by his alert imagination. Some are almost epigrammatic in their visual wit, while others are lyrical or even poignant. They may include a small farmhouse, a tractor heading almost diagonally up a sloping field, the sedentary pathos of an old man out walking with his dog, a yellow barn, or some small and outwardly charmless country sight. One element is quite inescapable in many of these idiosyncratic paintings – deep and genuine humour, a quality quite often found in painters as private people (including, most definitely, Blackshaw himself) but surprisingly rarely in their work.’7 But humour apart, an entirely new and imaginative, almost visionary element entered into works such as the ‘Angel’ series of 1989 — colourful, soaring and rapt – or the red horse already described. Certainly nobody else alive could have imagined these works, let alone painted them. And on a far blacker and more enigmatic note, the large Night Rider of 2001 is one of the high-points of his output and shows his flair for using a somewhat forgotten popular song.

However, even then we had not yet finished with Basil Blackshaw’s periodic metamorphoses. Just when he had established himself as a brilliant, original colourist and image-maker, his 2003 exhibition in Belfast threw a spanner into it all. At first glance these new works looked drab, almost fashionably ‘minimalist’, and even ostentatiously empty; a canvas such as Corner, for example, showed only a few peeling walls in washy monochrome, plus a dead area of empty floor. Could he be fooling us? Or was he consciously denying almost all he had stood for up to now ? But no, once again it seemed that he knew just what he was doing and in the end I came, almost reluctantly, to like these strange, dour pictures as much as I had liked their predecessors. With little colour, a few spare lines and some calligraphic scribbles, they have the power of suggesting a great deal beyond themselves.

There still remains a very important area of Blackshaw’s work which cannot be ignored; his portraits. These are spread over several decades and are much more consistent in style and approach than, say, his landscapes have been. Like the late Edward McGuire, he excels in painting or drawing fellow-artists, poets and the like, but he possesses far more natural fluency than McGuire, for whom the process was as demanding as a surgical operation. John Hewitt, Brian Friel, Camille Souter, the much-mourned David Hammond, the businessman and art patron Vincent Ferguson, Douglas Gageby (Fig 9) the great editor of the Irish Times, are among those he has depicted. In general, the treatment is quick, cursive and at times almost graphic, for the most part with minimal background or detail, but still conveying his sitters’ very contrasting identities with objectivity and insight. Various Antrim locals have also come within his sights, and in the mid 1980s he painted a remarkable Heads of Travellers series of a strongly Expressionist character. The fact is, if Blackshaw had painted nothing but portraits, he would still rank as a very good painter.

And to think that all these contrasting works, modes and subjects are the work of a single man living within sight of Lough Neagh, where his garden studio is his own small world in which he can shut himself like a monk inside a cell! He is no hermit, however; he mixes and chats with his neighbours, is geared thoroughly to the pace and habits of country living, keeps in touch with old friends, knows what is happening in the art world. To a local acquaintance he may talk about farming and the weather, but with a fellow-painter he may talk about Giacometti, a favourite and a considerable influence on him. He is interested in sport and, unlike so many artists and intellectuals, he does not hate or despise TV. Art, for him, is not the whole of life, but nevertheless it has dominated his mind and energies for more than half a century. The best Irish painter since Jack Yeats? More and more I find myself inclined to think so.

Brian Fallon is the author of An Age of Innocence: Irish Culture 1930-1969 (1998) and Imogen Stuart Sculptor (2001).

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 29, No 2, 2012