[slider_pro id=”185″]

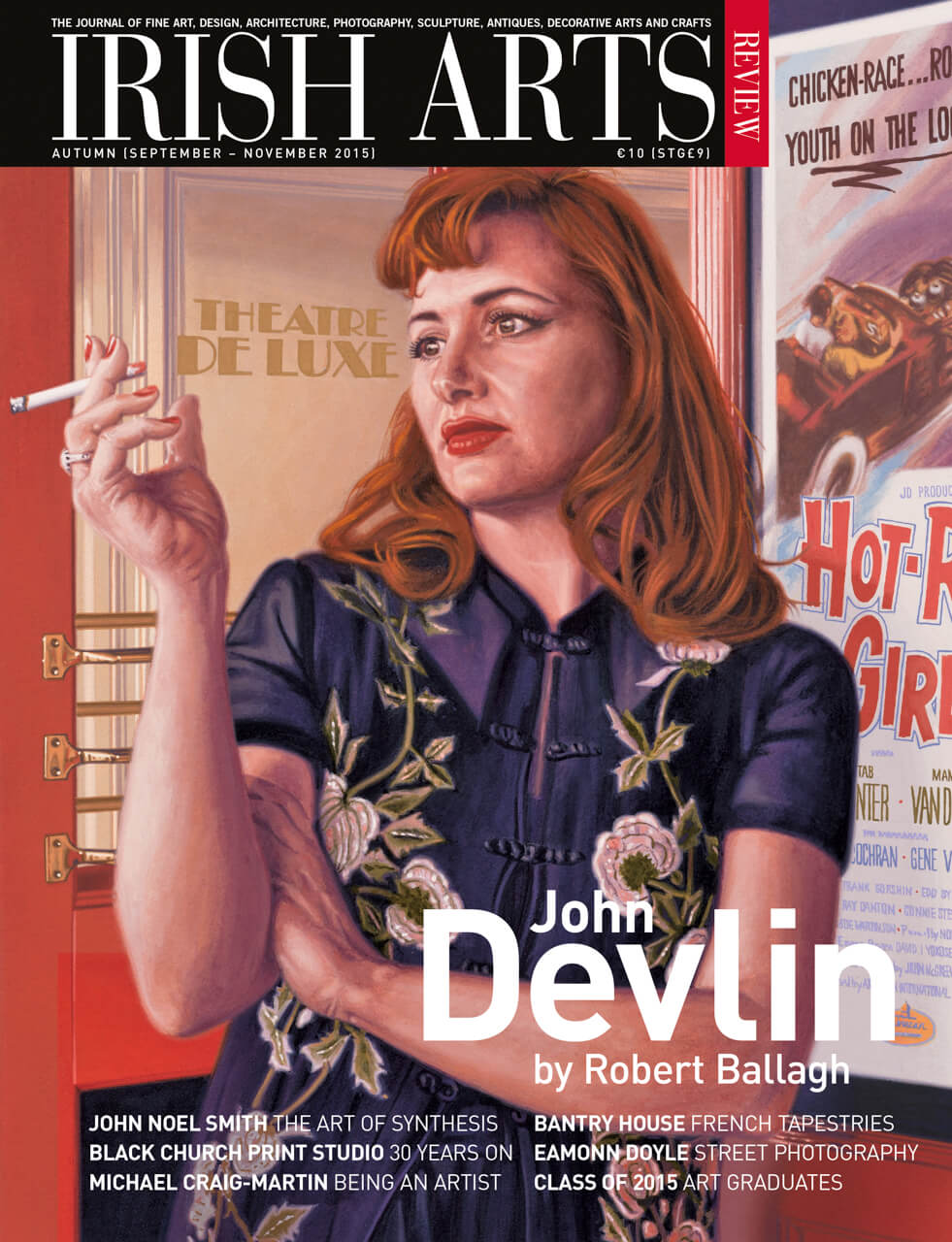

From the Autumn 2015 edition

Peter Murray gives the background to George Chinnery’s masterpiece, a portrait of the Kirkpatrick children, unhappy pawns in the politics of colonial India.

In the late heyday of the East India Company, a number of artists with close Irish connections, notably George Chinnery and Thomas Hickey, travelled to India seeking their fortune. Both artists painted the participants in two of the greatest tragic love stories of those times. The story revolves around James Achilles Kirkpatrick (Fig 4), a colonial administrator appointed Governor of Hyderabad, and the woman he met and fell in love with, Khair un-Nessa Begum, daughter of a powerful local ruler. In order to marry Khair, Kirkpatrick almost certainly converted to Islam. Renouncing British ways and customs, he adopted the manners, clothing and lifestyle of his wife’s family. The Muslim rulers of Hyderabad were refined and cultured; more so than the majority of East India Company officials, who were intent mainly on making their fortunes in the subcontinent.

In the late 18th century Hyderabad, capital of Telanga, (now Andra Pradesh) was one of the most magnificent cities in India. The centre of power for the Qutb Shahi dynasty, until captured by the Mughuls in 1724, it then became the home of the Nizams, a powerful dynasty created by Mughul Viceroy Asif Jah I. In 1694, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, fifth ruler of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, built the Mecca Masjid mosque, still one of the great heritage buildings of India. Khair came from one of the most powerful Nizam families of this cultured, refined and sophisticated city. Still in her teens, she was a Sayyeda, descended from a daughter of the first Shia Iman, Ali, and his wife Sayyeda Fatima. Kirpatrick was thirty-six when he and Khair wed. Although controversial, their wedding, and the respect Kirkpatrick paid to local customs and culture, was an important factor in winning the support of powerful families. Kirkpatrick’s lifestyle was not unusual; his counterpart in Delhi, Sir David Ochterlony, liked to be addressed by his Mughul title, Nasir-ud-Daula (Defender of the State), and regularly processed through Delhi with his private army and thirteen consorts, each mounted on her own elephant. An Irish general, Charles ‘Hindoo’ Stuart, liked to travel with his mistress, or ‘bibi’, and Brahmin priests. The core of the British Museum’s Indian collection was formed by ‘Hindoo’ Stuart.

In colonial India, there was no such thing as a private life. All marriages and relationships, to a lesser or greater extent, were deemed to be political and strategic.

Kirkpatrick was however remarkable for the enthusiasm with which he embraced Muslim life and culture. His lifestyle resulted in his incurring a great deal of official displeasure. In the free-booting days of the East India Company, from the mid 1600s through to the end of the 18th century, it was not unusual for European adventurers and colonial administrators to marry women from Indian families, but as the more censorious 19th century dawned, a new breed of administrators, among them Richard, Henry and Arthur, three Wellesley brothers from Ireland, were dispatched to India with instructions to bring a halt to this free intermingling of races and cultures. The new Governor of India, Charles Cornwallis (afterwards appointed Viceroy and Commander-in-Chief in Ireland at the outbreak of the 1798 rebellion) introduced regulations calculated to end interracial marriages and relationships. Henceforth, the children of mixed marriages were to be sent to England, to boarding schools, to be raised within a British environment.

In colonial India, there was no such thing as a private life. All marriages and relationships, to a lesser or greater extent, were deemed to be political and strategic. As gossip about Kirkpatrick’s secret relationship with Khair un-Nessa spread, a confidential Company investigation was set up by order of Richard Wellesley, Governor General of India. Colleagues of Kirkpatrick were summoned to Madras, to be interrogated on every aspect of his life, including his sexual life. The extent of Kirkpatrick’s relationship with Khair-un-Nissa Begum was revealed and an order was given for the relationship to be broken up. Their two young children, Sahib Allum and Sahib Begum, were to be sent to England to be educated.

In August 1805, while Sahib Allum and Sahib Begum were staying in Madras, at the house of Kirkpatrick’s maternal uncle William Petrie, their portraits were painted by George Chinnery (Fig 2). It was an important commission for the artist, who had arrived in Madras some two and a half years beforehand, and was staying with his brother John. Chinnery’s move to India was not unusual; other European artists such as Johan Zoffany and Francesco Renaldi, were also seeking to establish lucrative practices in India, receiving patronage as much from Mughul and Hindu families, as from European settlers. However Chinnery stood out amongst these artists for his slightly mad behaviour. He was described by the lawyer William Hickey as ‘. . extremely odd and eccentric, so much so that at times to make me think him deranged . . . When not under the influence of low spirits, he was a cheerful, pleasant companion, but if hypochondriacal was melancholy and dejected to a degree.1 While Chinnery may have been mentally fragile, his brother was far more seriously affected by the same condition and was eventually incarcerated in the Madras Lunatic Asylum.2 Among the many Chinnery drawings in the British Library is one depicting Arthur Wellesley being received at Madras by the Nawab ‘Azim al-Daula.

one of the finest portraits in the National Gallery of Ireland is his 1787 portrayal of a young Bengali Muslim woman, said to be ‘bibi Jemdanee’, the common-law wife of William Hickey

Born in London in 1774, Chinnery had studied at the Academy schools before moving to Ireland, age twenty-two, where he painted portraits for a relative, Sir Broderick Chinnery, MP for Bandon. In 1799 he married Marianne Vigne, daughter of a jeweller in College Green, Dublin, where he had lodgings (Fig 8). Although they had two children, the marriage was not a success, not least because of the artist’s liking for Dublin’s theatre and social life. His portraits from this period, painted with spirit and bravura, include Hugh Douglas Hamilton and the lawyer Ninian Mahaffy. In 1800 he helped organize the Dublin Society’s Drawing Schools, and also revived the dormant Society of Artists of Ireland. In addition to portraits of notables such as ‘Buck’ Whaley, Chinnery painted literary subjects, including Satan’s Arrival on the Confines of Light, inspired by Milton’s Paradise Lost. However, while his work was praised in Ireland, Chinnery’s restless spirit led him to depart for London in 1802, and then to India.

However, notwithstanding, or perhaps because of Chinnery’s imaginative powers, the portrait he conceived of Sahib Allum and Sahib Begum is a masterpiece. Depicting both children standing on steps in front of a heavy curtain, it is in no way stereotyped or formulaic. Standing beside his younger sister, dressed in gold-embroidered silk robes, and wearing strings of pearls, dark-eyed Sahib Allum gazes with confidence at the viewer. In contrast, the downcast eyes of Sahib Begum convey her deep sadness at their being parted forcibly from their mother. On 15 October, shortly after the portrait was completed, James Achilles Kirkpatrick died, broken-hearted, while on a visit to Calcutta. He was forty-one years of age. It seems that, notwithstanding efforts by Khair to secure ownership of the painting, depicting her two children who she knew she would never see again, it passed to Kirkpatrick’s private secretary Henry Russell. For a time, it seems, Khair became the lover of Russell (also the subject of a portrait by Chinnery), before she too died, in 1813. The fate of her son Sahib Allum was particularly tragic. Not long after arriving in England, he fell into a vat of boiling water and was so badly injured that one of his arms had to be amputated. He lingered on for some years, taking a keen interest in poetry, before he died. The Chinnery portrait was brought to England, where Khair’s daughter Sahib Begum, the only surviving member of the family, looked after it. In 1829 Begum married Captain James Winslowe Phillips, and at the beginning of the following century, when Walter Strickland was compiling his Dictionary of Irish Art, he noted the portrait being in the collection of a ‘Mrs. Phillips’. It is now in the collection of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC).

Another painting from this period, by an Irish artist working in India, gives an equally compelling insight into the fusion of cultures of East and West. A relative of William Hickey, Thomas Hickey was also seeking his fortune in India. Born in Dublin, the son of a confectioner from Capel Street, he had trained in the Dublin Society’s Drawing Schools. In 1780, he received permission from the East India Company to go to India, and after some extraordinary adventures, bearing letters of introduction from Sir Joshua Reynolds to Warren Hastings, finally arrived in Calcutta in 1784. His career flourished, and one of the finest portraits in the National Gallery of Ireland is his 1787 portrayal of a young Bengali Muslim woman, said to be ‘bibi Jemdanee’, the common-law wife of William Hickey (Fig 6). A lawyer in Calcutta, Hickey was delighted with Jemdanee, who ‘lived with me, respected and admired by all my friends for her extraordinary sprightliness and good humour . . . She was as gentle and affectionately attached a girl as ever a man was blessed with . . . Unlike the women in general in Asia she never secluded herself from the sight of strangers; on the contrary, she delighted in joining my male parties, cordially joining in the mirth which prevailed, though she never touched wine or spirits of any kind.’3 However, when Zoffany returned to Calcutta in 1786, Thomas Hickey’s career declined and so he embarked on further adventures, accompanying Lord Macartney to China on a diplomatic mission (See Peter Murray, ‘Strangers abroad’ Irish Arts Review, Autumn 2013 p.119).

The lives and deaths of these colonial administrators and Company officials, chronicled in William Dalrymple’s book White Mughuls, published in 2002, are also recorded in public buildings and Christian churches throughout India. In St Mary’s, Madras, a church designed by William Dixon and completed in 1680, the christening of James Achilles Kirkpatrick is recorded, as is the marriage of Henry Russell to Jane Amelia Casamaijor. However, Casamaijor died in 1808, aged nineteen, within four months of their marriage. The death of the equally young Khair, some years later, brought to an end a similarly short-lived relationship. In Calcutta, in St John’s Church – a building based on St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Kirkpatrick Memorial, sculpted by John Bacon Jnr and erected in 1808 by his ‘afflicted Father and Brothers’, a verse carved on the lower panel celebrates the power of art to transcend life and death, and concludes, ‘Hope built on Faith, Affliction’s Balm and Cure/Divinely whispers ‘‘Their reward is sure” ‘.

Peter Murray is Director of the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork.

1 The Memoirs of William Hickey, ed Alfred Spenser, (4 VolsLondon 1913-25) vol IV, p. 385.

2 Patrick Connor George Chinnery 1774-1852: Artist of India and the China Coast (London 1993), p. 87.

3 William Hickey (ed. A. Spencer) The Memoirs of William Hickey (London, 1925), Vol. III, p. 327.