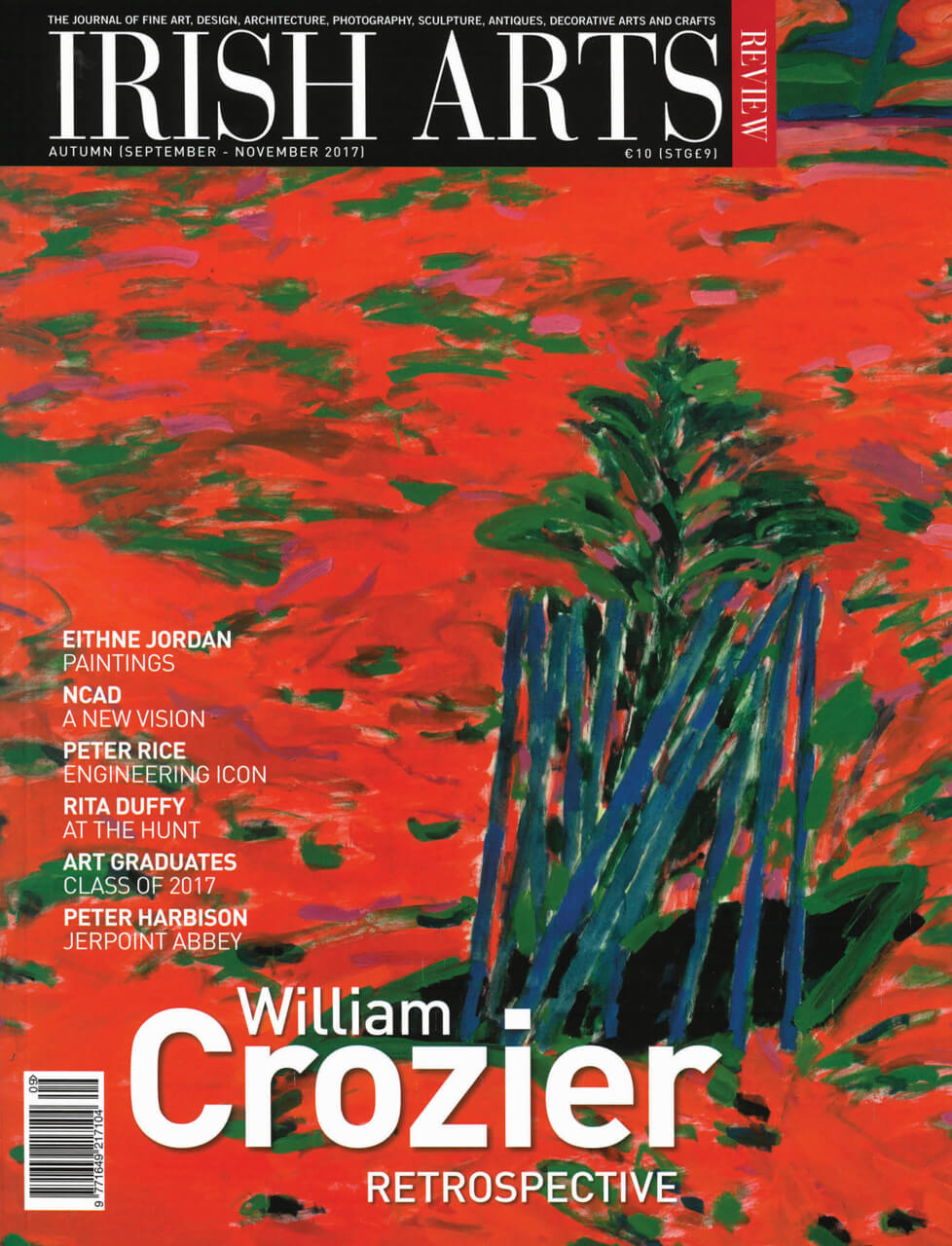

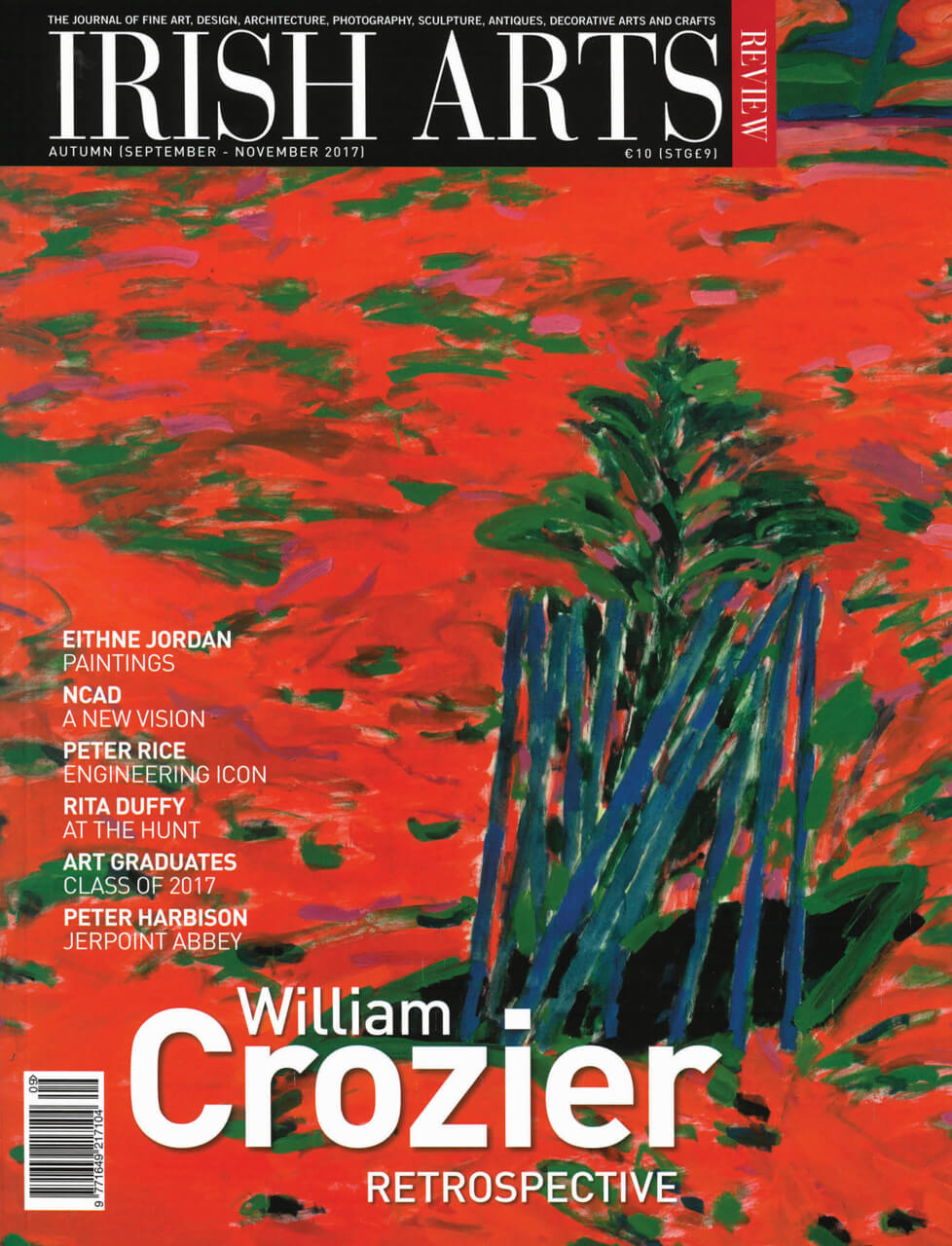

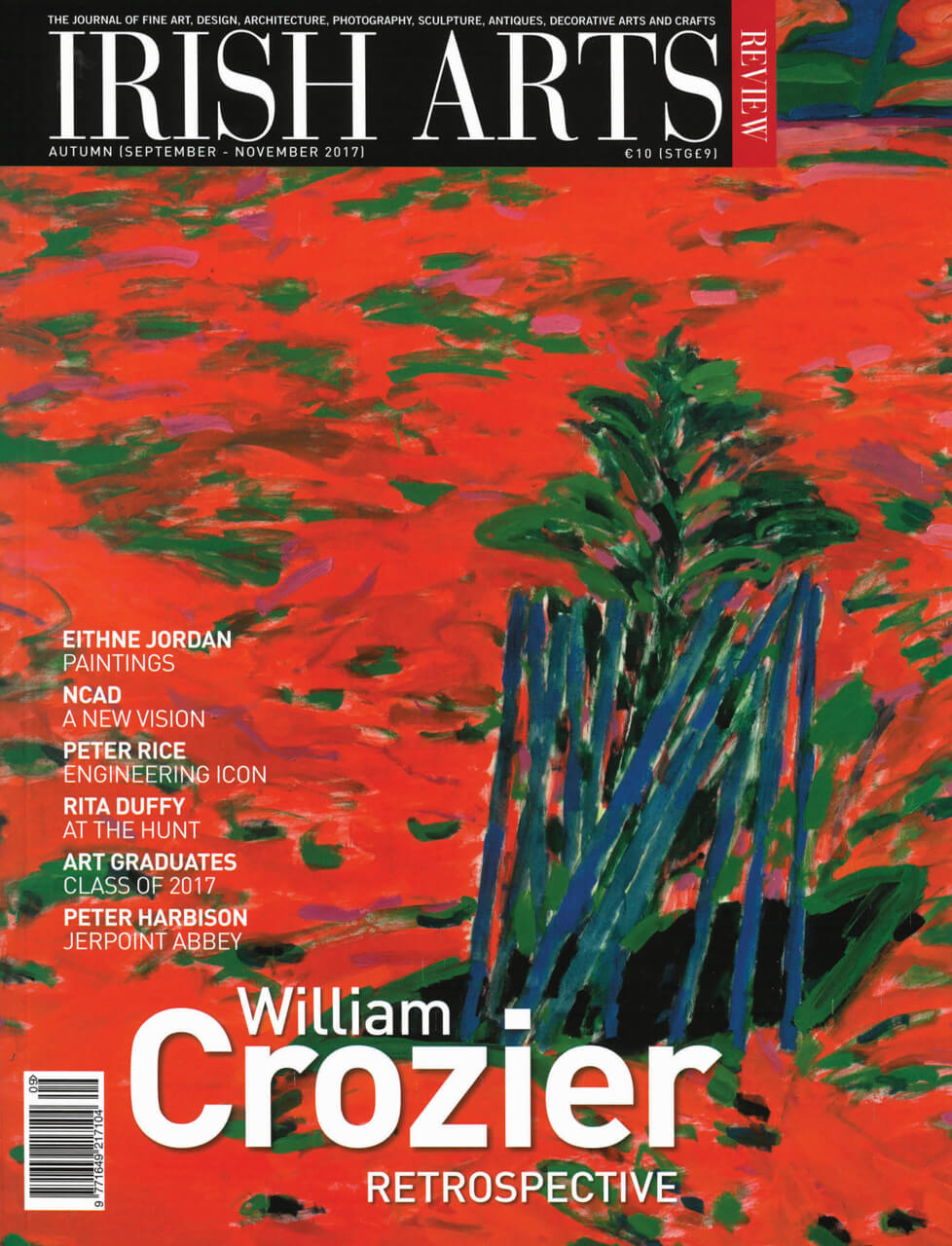

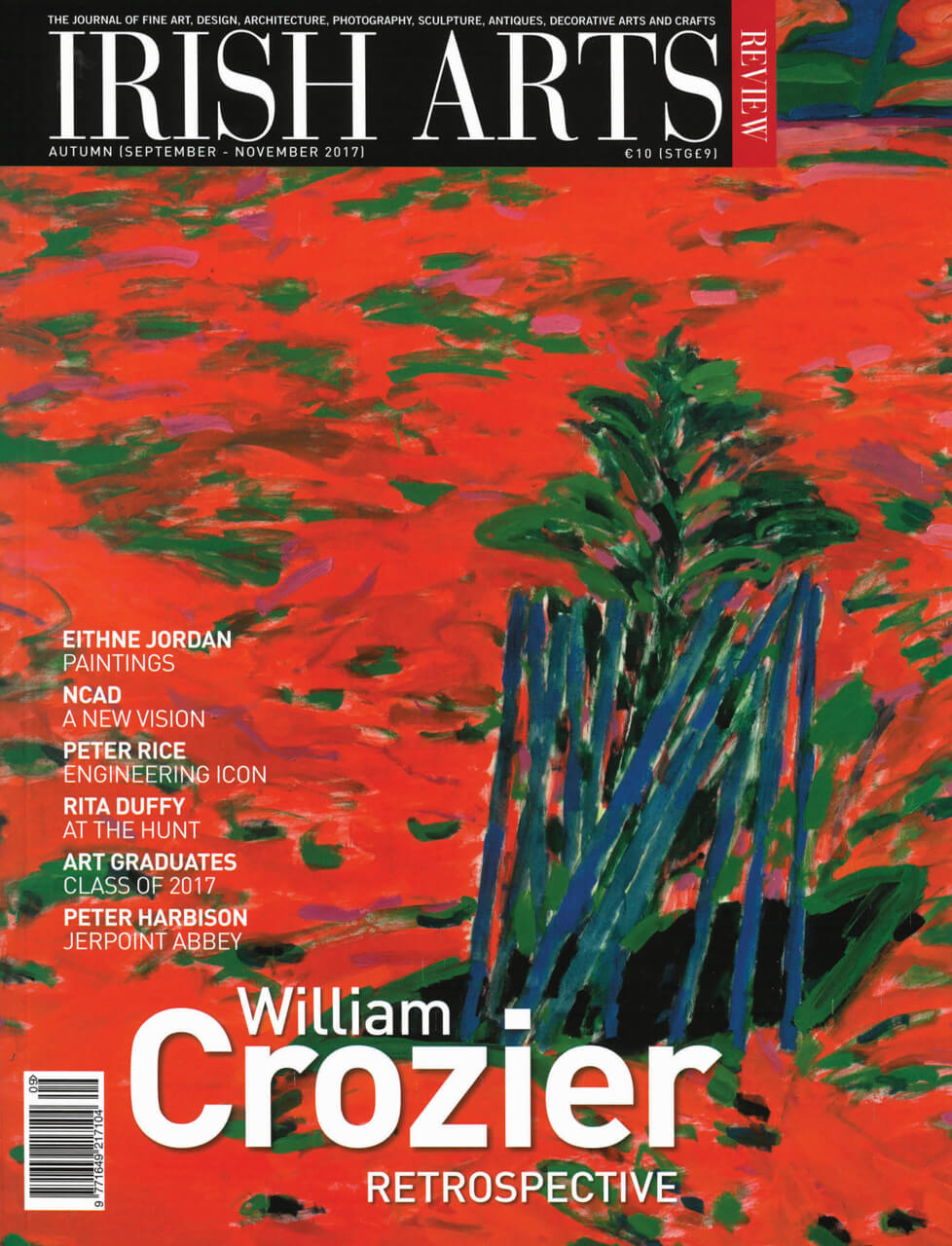

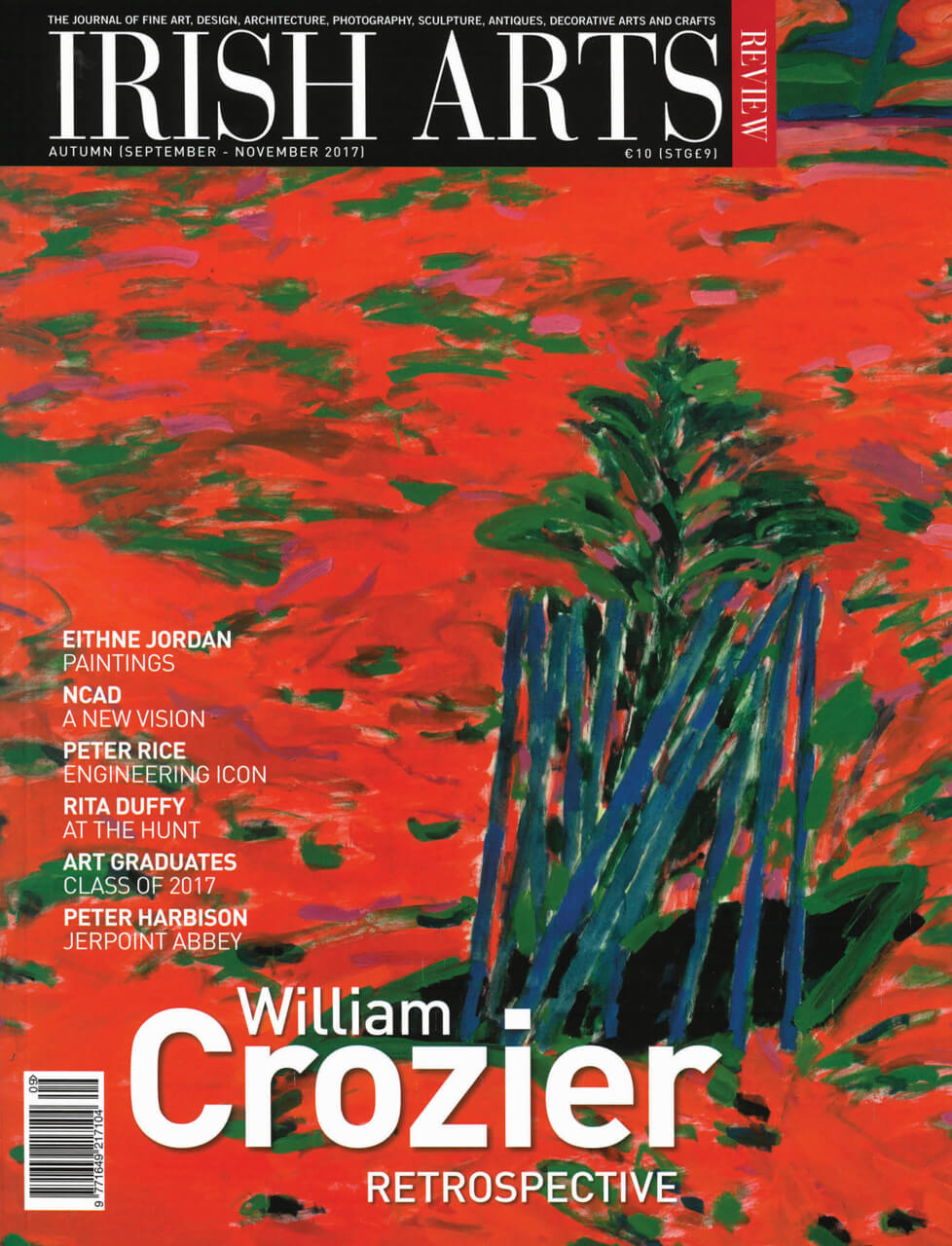

Seán Kissane examines the early career of William Crozier as West Cork Arts Centre and IMMA celebrate his work with complementary exhibitions

In 1985 William Crozier sprang onto the Irish cultural stage when his painting The Rowan Tree (1982) won first prize at the exhibition ‘Cork Art Now’ at the Crawford Art Gallery (Fig 5). Billed as a major survey of Irish art, it is notable that Crozier’s picture was neither made in Ireland nor had an Irish subject; but indicative of the way that he was fully embraced as an Irish artist when he began to exhibit here in the mid 1980s. The works that Crozier went on to make in Ireland, the classic ‘West Cork’ pictures, quickly became iconic, as though the Irish audience was now seeing the landscape for the first time through his eyes; but to some extent these works were seen in isolation, without consideration for his previous artistic output. Considering the vivid lyricism and joyful palette of these Irish paintings, Crozier’s work of the 1950s and 1960s might have surprised for its dark palette and expressionist content. The exhibitions at West Cork Arts Centre and IMMA address this duality in his practice by firstly showing his well-loved Irish works close to where he made them, followed by a presentation of the less-familiar early paintings at IMMA in the autumn.

Born in Scotland in 1930, Crozier had already had a distinguished career of three decades by the time he and his wife acquired a house in West Cork in 1983. He was committed to the idea of a European tradition in painting, something that went against the prevailing trend of Abstract Expressionism coming out of New York that dominated discourse in Britain in the late 1950s and 1960s. While still in his teens he and his friend the artist William Irvine went to Paris where they saw an important exhibition of Picasso’s war-time art. This experience affirmed his desire to become an artist and he enrolled in the Glasgow School of Art in 1949. The teaching in Glasgow was firmly based on the French atelier system with drawing at its centre. Although it was clear to him that this was out-moded, he valued the training and discipline it offered and he graduated with distinction in 1953. While still an undergraduate he befriended the ‘Two Roberts’, Colquhoun and MacBryde, who were identified with the neo-Romantic movement, although their work was darker and imbued with the spirit of the post-war years. Colquhoun in particular was very influential on the young Crozier and some examples of his early work clearly pay homage to the older artist. But this was a time of experimentation in Crozier’s life and he moved from work inspired by Colquhoun to Picasso, Mondrian and later to Dada-inspired assemblages. He visited Ireland a number of times during this period, and he also visited Paris again in 1950 and 1953 where he sat in Café Les Deux Magots opposite the leaders of the Existential movement Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, but despite being in thrall to their writings was somewhat star-struck and too shy to approach them.

At the age of twenty-five, he moved to Dublin where he quickly became aware of leading Irish artists through his friendship with Victor Waddington who represented Jack B Yeats, Patrick Swift, and Louis le Brocquy. He was Crozier’s only connection to the visual arts at that time, as he met few painters and made no friends with artists.1 Instead, he made deep connections in the theatre and literary scene. Supporting himself and his young family through painting theatre sets, he soon found himself in McDaid’s Bar, which was the centre of literary circles – Dublin’s Les Deux Magots – where Patrick Kavanagh and Brendan Behan were the figures that loomed largest. In his 1976 memoir about his friendship with Behan, Dead as Doornails, Anthony Cronin recounts many tales of the excitement, chaos and sheer alcohol-fuelled lunacy of the time. This must have appealed to Crozier, as he described his practice in the early 1950s in the following terms:

I was at the beginning of an anarchic enthusiasm, fuelled by the work of the Dadaists. My materials were the flotsam and jetsam of the street. The more dissimilar it was from ‘ART’ the better. I eschewed the traditional materials of the artist and what I considered to be its values. In retrospect I now see that I was abandoning and eliminating the baggage of my skills and training, shocking myself, trying to establish my credentials as a contemporary, even a modern.2

Crozier was an artist with an obsessive focus – he could make hundreds of images from a single motif and then suddenly abandon it

Returning to England in 1956 he reconnected with the Two Roberts who were at the centre of London’s Soho scene that included Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. Crozier participated in a group exhibition at the Parton Gallery showing the Dada-inspired assemblages described above. At this time he also began to paint the landscape but in an anti-Romantic and austere manner. He used materials that were beyond the traditional, like household gloss paint on panel for their mundane and anti-art qualities, a feature shared with the radical arte-povera movement. By his late twenties he had a successful career in London with a contract with the Drian Gallery and later with Tooth’s. He was not above courting controversy, most infamously when he titled a large painting, A Portrait of Princess Margaret (Fig 1). Some of the resulting press described the work as ‘disgusting’ and went on to quote Crozier as saying that his next portrait would be of Sir Oswald Mosley ‘because I hate him’.3 This was almost certainly a Dada-like act of deliberate provocation on the part of the artist for the painting in question is a large abstracted landscape or a ‘still-life’ as described by its current owner, the National Museum in Gdansk. The bleak views of the British landscape seen in later works like Essex Landscape (c. 1959) are imbued with a darkness and pessimism that is immediately apparent. Appearing like cross-sections through the land they are like forensic examinations of the place and time. His friend the poet Anthony Cronin wrote about this period thus:

It is difficult to describe it now and to describe the kind of malaise that hung on the air; difficult also to decide on the reasons for this: was it the bomb that hung over people’s heads? Was it the camps? I think the worst thing about the camps was the view, the aspect of human nature they revealed. It wasn’t so much the suffering of the victims, but the appalling view of human nature we were forced to contemplate and indeed have been forced to contemplate ever since in new contexts.4 Cronin’s description of the (atom) bomb and the (concentration) camps is of vital importance when considering Crozier’s work up until around 1975. It offers a way of reading keys works from the early 1960s such as, Self-Portrait, (Ruth Borchard Collection); Flanders Fields (National Gallery of Ireland), and Bourlon Wood (Fig 2). The image of the screaming head with the flesh apparently burning from the bones could be an imagined scene from Hiroshima. But there is also a clear continuity of practice from the Essex landscapes shown as a cross section through the land. But here a brutal discovery is made as the body of a soldier is found interred, complete with his helmet still in place. It is grisly, like a dead animal in a field; some folds of skin and flesh remain on the bones. And what of the red bed on which he lies? It is reminiscent of medieval execution by fire like Titian’s Martyrdom of St Lawrence (1559) but rather than the martyr’s salvation it suggests an unquiet death. Bourlon Wood (Fig 2) was acquired recently by the Imperial War Museum in London showing that the eye-witness accounts of ‘official’ war artists like William Orpen and Paul Nash are now being added to with works by those who were not present on the battlefield but whose lives were affected nonetheless. In a later image Crossmaglen Crucifixion (1975), he uses similar strategies to address the atrocities of the Troubles in Northern Ireland (Fig 6); while Portumna (1962) addresses the subject of the Great Famine. Crozier’s images seem to deal with the ghosts of these people or their undead spirits. It is always a single individual that we see, that existential figure of the outsider, demonstrating his deep engagement with the writings of Sartre and de Beauvoir.

Returning to London from an extended period in Spain in the mid 1960s he found that the seriousness of his work was out of step with the prevailing fashions for American abstraction and Pop-Art. He began to teach and in 1968 was appointed Head of Fine Art at Winchester School of Art where he would remain for the next twenty years. The landscape around Winchester effected a change in his image making. He created paintings in the grand European style with large gestural canvases, often made in one day that described his surroundings. At this time he also abandoned the use of the body or skeleton saying that he had begun to ‘manufacture the quality of torment and isolation’.5 Significantly he also admitted that the landscapes that followed were the same scenes but without the skeletal figures. Instead he looked to his great hero Kazimir Malevich and Russian icon paintings to find new ways to create intensity without resorting to the human body with its narrative qualities. He also looked to the 17th century to Nicholas Poussin and Claude Lorrain for their formal compositions and quality of stillness.

It was with all of these seemingly contradictory influences that he arrived to West Cork in 1984 and began to take on the Irish landscape (Fig 4). Crozier was an artist with an obsessive focus, he could make hundreds of images from a single motif and then suddenly abandon it. West Cork came to him at a time when he was ready for a new challenge and the work he made there was quite unlike much of his early work for its apparent lyricism and joyfulness. The exhibitions at IMMA and West Cork Arts Centre aim to demonstrate the continuity in his practice and show a different side to this iconic artist.

‘William Crozier The Edge of Landscape’ IMMA, Dublin 13 October – 8 April 2018

Seán Kissane is curator of exhibitions at IMMA.

1 William Crozier Archives MS9 (Dublin in the 1950s.)

2 Ibid.

3 The Bulletin, September 24, 1958 p. 16

4 Anthony Cronin. Address to the Aosdána General Assembly. 19 April 2013.

5 Crozier interview with Ian Kirkwood. Artlog no 5. London 1979. P4