Is there a School of Limerick? Niamh NicGhabhann considers the question. Charles Harper’s work is included in the RHA Annual Exhibition, until 11 August.

Limerick is a complicated place – a city of fine-boned fanlights set in red brick frames, angular spires outlined against grey skies, and overgrown bow lanes; a city that sounds like hooves hammering on tarmac, and oars cutting through water. Whittled down to two images, the city could be represented by the river and the grid, a constantly overlapping set of relationships between nature and structure. For anyone growing up among the visual art landscape of Limerick, these two images will also bring to mind the work of Charles Harper RHA – long oars crossing in an intricate pattern on a plane of rich colour, or a strange and intriguing series of near identical heads, formed from quick, economical paint strokes, arranged in a grid pattern. Born on Valentia Island in 1943, Harper’s body of work reflects both his individual negotiation of colour, structure and form in paint, as well as broader regional, national and international artistic developments. Throughout the profiles of Harper published during his career, his personal commitment to honing an aesthetic of ‘honesty’ in his work is repeated. In an interview with John Hutchinson published in The Irish Times in 1983, he stated that ‘good art is responding clearly, with vision, to your own self and environment’.1 In an earlier interview with Harriet Cooke in the same newspaper, published in 1972, Harper is quoted as saying that ‘I’m not someone who’s going to break any barriers, I simply want to be accurate – in painting and in relation to myself’.2

The work selected for the RHA retrospective of Harper’s painting reveals a life dedicated to art

Although he eschews the idea of overt social commentary in his work, and resists being incorporated or organized into any particular ‘group’ or ‘school’ of Irish painting, Harper has been central to the emergence of structures supporting and maintaining the visual arts in Ireland since the 1960s. He was a student at the National College of Art (NCA) in Dublin during the mid 1960s, a period of considerable change and tension between staff and students, who saw the NCA, the Royal Hibernian Academy, and the Irish Exhibition of Living Art as elitist, restrictive and old-fashioned. He was presented with his first major award in 1965 for an etching, titled Inferno, by the Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Dublin as part of their celebration of the life and work of Dante Alighieri. Although Harper was also critical of conservative arts organisations, he participated in the Irish Exhibition of Living Art in 1971, winning the £400 Carroll Open Award for his painting Media Projection, one of many prizes awarded during his career.

He was centrally involved in the major visual art developments in Dublin during the early 1970s, including the establishment of the Project Arts Centre in Essex Street, acting as a committee member and selector for the Oireachtas Art Exhibition, and later, becoming a founder member of Aosdána in 1982. Following his move to Limerick in order to take up a teaching position at the Limerick School of Art and Design in 1975, he was part of the founding committee of the Exhibition of Visual Art (EVA), later EV+A and now EVA International. This exhibition, which celebrated its 40th birthday in 2017, has consistently created an experimental forum for Irish artists to show their work in conversation with a wide range of international artists, selected and curated by figures such as Jan Hoet, Katerina Gregos, Annie Fletcher, and Koyo Kouoh. This expansive forum for thinking about and producing visual art, sustained in Limerick by a committed group of artists, board members and arts managers, has had a profound impact on the visual arts in Ireland. The list of contributors to the first decade of EVA exhibitions provides a valuable context for the development of Harper’s own work during this period, and the first edition, 77, included figures such as Eilis O’Connell, Nigel Rolfe, David Lilburn, John Shinnors and Maria Simonds-Gooding.3

Given the importance of EVA and the energy that it brought to Limerick on an annual basis (shifting to a biennale structure from 2010), it is possible to posit the existence of a Limerick aesthetic or ‘school’ of art that developed from the late 1970s onwards, represented by the artists who have made the city and region their base, often teaching in the Limerick School of Art and Design, as well as those artists who have gravitated to the city as participants, students and audience members for the period of the exhibition over the past forty years. Indeed, the emergence of vibrant new structures such as Ormston House Gallery and Askeaton Contemporary Arts are part of this experimental legacy in the region. A research project exploring the wide-ranging impacts of EVA on the development of visual art in Ireland is surely overdue, but it is possible to observe connections between the work of Harper and his contemporaries who have been, or who are, based in Limerick, including John Shinnors, Diana Copperwhite, Samuel Walsh and Jack Donovan in particular, as well as in the work of figures such as Vivienne Bogan and Tom Fitzgerald, also living and working in the region.

The use of the grid, combined with multiple iterations of a similar image or icon, is particularly important to Harper’s work

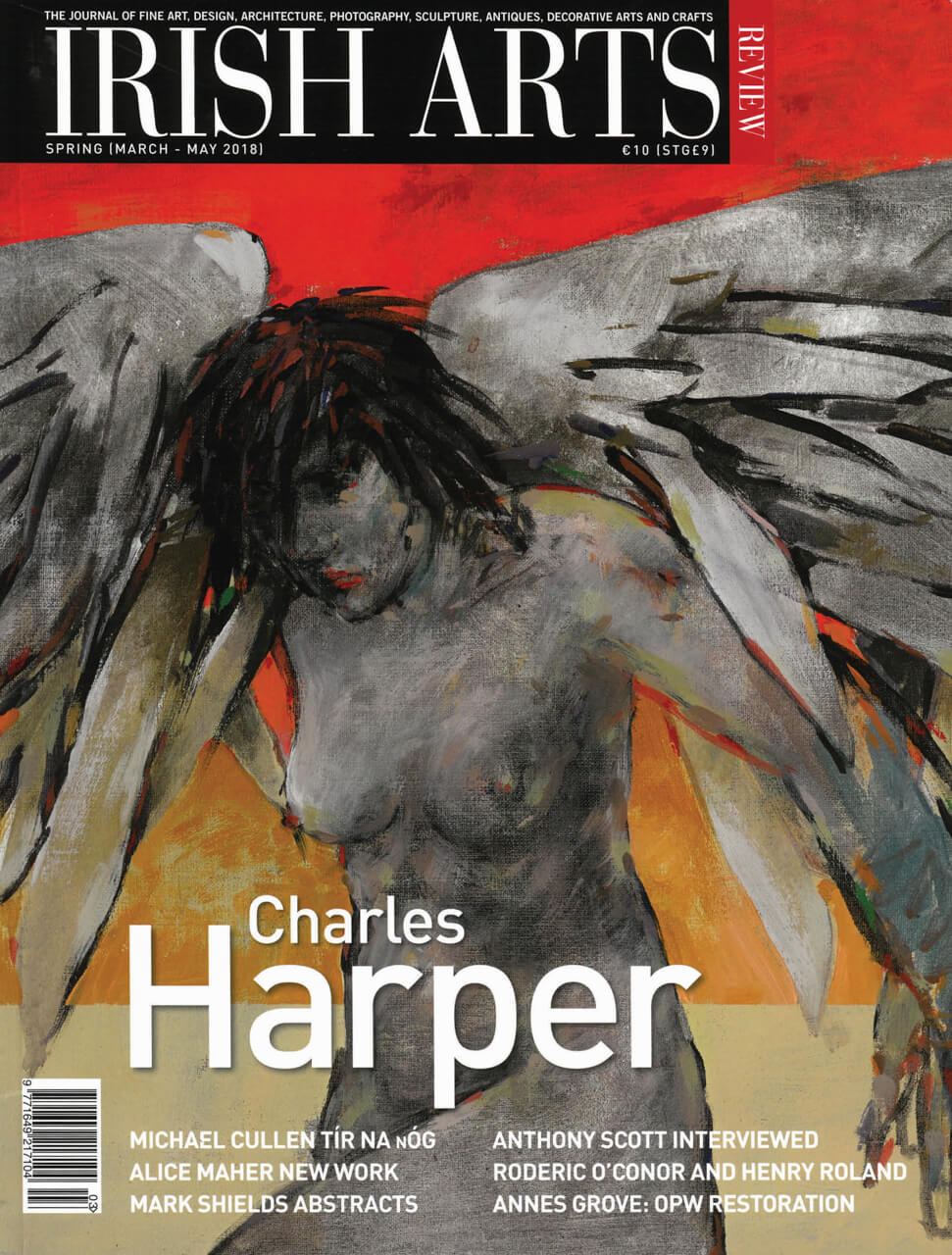

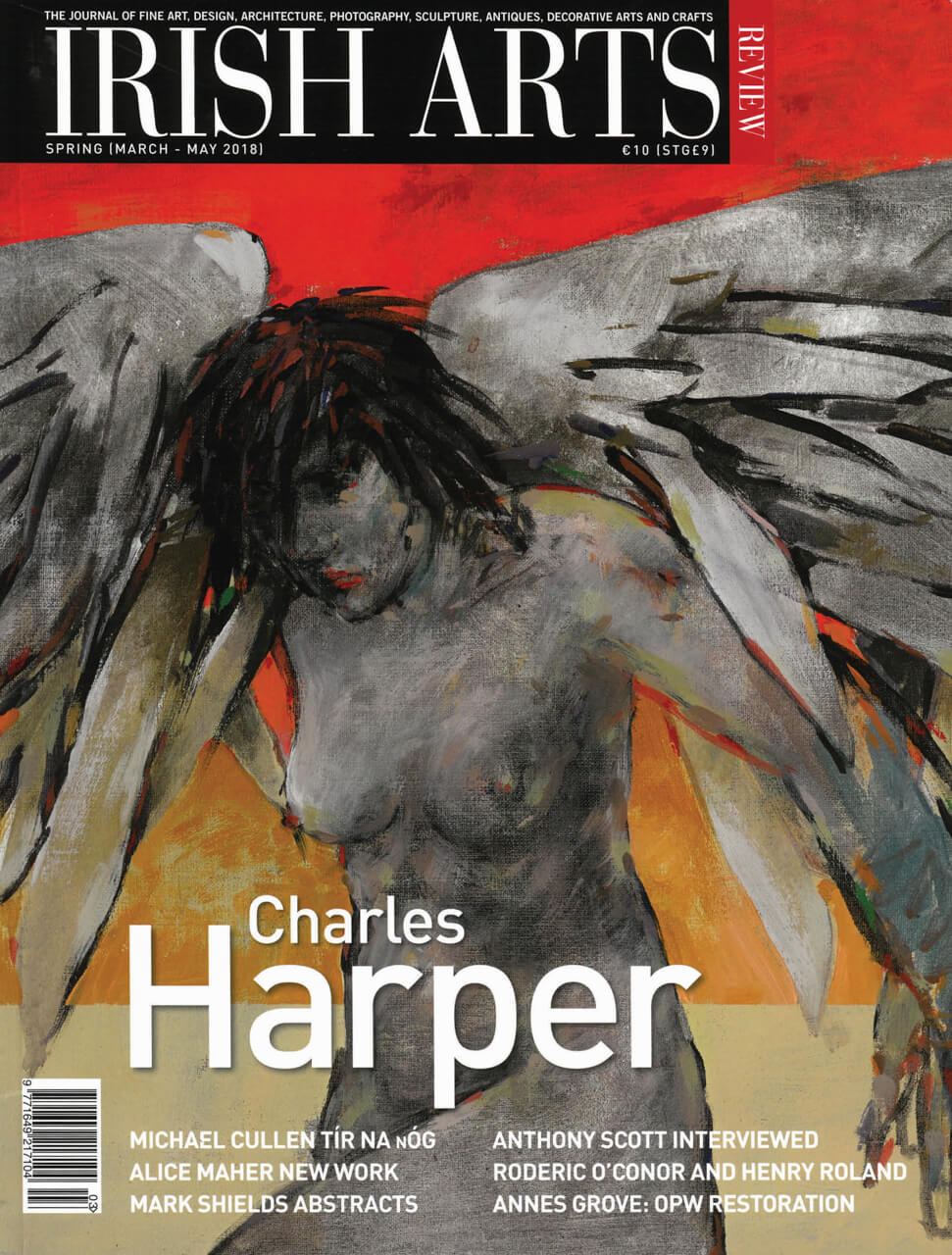

Charles Harper’s work can certainly be considered in the broader context of Irish painting. His ‘Angel’ series of paintings (Figs 3&10), including oil on canvas and watercolour on Japanese paper, from the mid 2000s, bring to mind the formal and tonal arrangements of certain works by Basil Blackshaw and Barrie Cooke. A series of busy and colourful works from the mid 1980s and early 1990s, including Unnoticed Epic from 1990, which layer grids and figurative elements, perhaps can be viewed as being in conversation with figures such as Micheal Farrell, while his delicate graphic style is reminiscent of the work of Tom Fitzgerald. His quick, fluid and sculptural brushwork as a painter, and use of vivid colour highlights, also reflects the influence of Louis le Brocquy. In interviews, Harper has mentioned Harry Kernoff, Patrick Collins and Francis Bacon as artists he admires, and noted the particular impact of an exhibition of work by Mark Rothko at the Tate, London, describing a ‘very full feeling from these apparently empty works’.4 However, the tension between figuration and abstraction throughout Harper’s oeuvre, fused with an intense use of deep, glowing and rich colour, places him in immediate conversation with John Shinnors. The formal and tonal relationships established throughout the best of Harper’s painting can also be considered beside the abstract paintings and drawings of Samuel Walsh, whose work moves between strident and lyrical registers of colorito and disegno. At the other end of this spectrum between abstraction and figuration sits Jack Donovan, who was an influential presence within the Limerick visual art community, and whose gently surreal, tremulous interpretations of the human form, and the head in particular, can be reflected in Harper’s own treatment of the human figure.

The work selected for the RHA retrospective of Harper’s painting reveals a life dedicated to art, and to a continual and ongoing exploration into the development of a durable and meaningful visual language. The earliest work in the show, Abstract, from 1962 (Fig 8), reflects the artist’s desire to move beyond the careful, elegant application of paint that had characterised much of his early artistic training. The thick, textured application of paint, and arrangement of black block forms on a two-tone ridged and scored background, also bring to mind the influence of the work of German Expressionist painters that Harper encountered during a pivotal period of training at the Fisherkoesen Film Studios in Bonn in the late 1950s. Execution, which was a prize-winner in the 1966 Dublin Municipal Gallery exhibition to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising in Ireland, will be of great interest to those who engaged with the centenary commissions and artistic responses produced throughout 2016. The extant version of Execution, which is actually a reproduction of the original work that was damaged in storage, depicts the moment of James Connolly’s death by firing squad as he falls from his chair (Fig 9). The inclusion of gun barrels in the lower right-hand corner of the work, and the toppling figure of Connolly, asymmetrically positioned across the scumbled surface in the upper left-hand space of the canvas, results in a tense stand-off between stillness and action, commemorative symbolism and narrative depiction. Although the painting represents a recognizable moment within the near mythical events of 1916, it is primarily expressive through its surface qualities. The textured surface, which brings to mind both a stone ground and the blankness of time past and life lost, occupies the centre of the canvas. The figure of Connolly, outlined as a single graphic icon, is marked with cross-shapes and daubs of dark green-grey paint, representing camouflage, but also reinforcing the sense of his body as an abstract icon or symbol.

During a studio visit carried out while writing this piece, Harper spoke about the idea that meanings and interpretations are constantly in flux, changing continually for artists, critics and audiences alike. The completion of a work is complicated for Harper, who returns to his paintings continually, and this may explain the importance of series throughout his career. The repeated attention to, and interpretation of, specific motifs and ideas throughout his paintings – the boat and oarsmen, the head, the grid, the angel, and, in more recent years, the graphic, linear qualities of the Burren landscape – have allowed him to build a strong visual language which can be changed or retuned in order to express and to communicate different ideas. The use of the grid, combined with multiple iterations of a similar image or icon, is particularly important to Harper’s work. The grid, he explains, allows formal discipline to be established on the canvas, with each square carefully measured out. This discipline then creates the space for inventive and creative interpretation of the idea being explored – from a sequence of hooded monks to the bandaged, constricted heads of the ‘Confined Citizen’ series (Fig 2). In responding to Harper’s use of the grid format and the repeated image, critics have noted the possible influence of Eadweard Muybridge’s photograph series, available to Harper as a student, and also the similarity of these grids to film strips, reflecting his early training in the medium.5

Throughout many of the grid paintings, a central spire form anchors the work, usually painted in a darker colour, creating a vertical axis that can also be observed across many of his strong, graphic boat race images. This series is balanced between figuration and abstraction through the combination of carefully defined bodies and the glowing, textured background and linear patterning of the oars. While Harper’s skill as a draughtsman is evident, his work moves beyond the representation of the visual world to the creation of symbols, images that are anchored to reality but that have been whittled down by the artist to a new form, changed yet remaining recognizable to the viewer. Speaking about the heads depicted in his grid paintings, he described them to me as ‘re-visions’ – glimpses of past faces known to the artist that emerge and take form through the quick action of the paintbrush. Harper’s works, therefore, could be described as occupying a middle point between the subjective imagination of the artist and the shared visual experience of the world. This balancing act was described by critic Gerry Walker as ‘controlling sets of divergent impulses’, resulting in work that ‘avoids rigidity by means of an inclusive, counterbalancing, organic lyricism’.6

Charles Harper’s work as a teacher and an organizer certainly deserves attention in the history of Irish art, but it is fitting that his own body of work is to be examined and celebrated through this retrospective exhibition at the RHA. The opportunity to bring his work together – much of it in national and international public collections – will allow viewers to explore a lifetime of individual commitment to art-making, and life-long determination to respond, in paint, to the times we live in.

‘Charles Harper – A Retrospective’ RHA, Dublin 16 March – 22 April 2018.

Niamh NicGhabhann is an art historian and lecturer at the University of Limerick, where she is the course director of the MA Festive Arts programme.

1 ‘Through the grid’ The Irish Times, 18 Feb 1983.

2 ‘Studies: Harriet Cooke interviews the painter Charles Harper’, The Irish Times, 21 Sept 1972.

3 The catalogue for the first EVA exhibition has been digitized and is available online:

https://www.eva.ie/1977

4 ‘Studies: Harriet Cooke interviews the painter Charles Harper’, The Irish Times, 21 Sept 1972.

5 Charles Harper, Gerry Walker and Aidan Dunne, Profile Charles Harper (Kinsale, Co. Cork: Gandon Editions, 1998), p.14.

6 As note 5 p. 6.