Paula Murphy examines the background to Oisín Kelly’s immortalization of Big Jim Larkin commissioned by the workers of Ireland

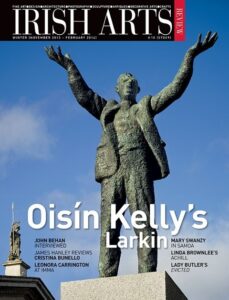

A quotation that dates back to the French Revolution – The great appear great because we are on our knees. Let us rise!1 – is inscribed in English, Irish and French on the front of the pedestal that supports the statue of James Larkin (1874-1947) in the centre of Dublin. The monument is located close to the site of the former Imperial Hotel (now Clery’s), from a window of which Larkin famously communicated with the people of Dublin in 1913. However this was not the first position in Dublin, or the first memorial that was proposed for a Larkin commemoration. In the aftermath of his death and the establishing of a memorial fund, proposals to commemorate Larkin included a Memorial Hall and a gravestone in Glasnevin cemetery, with designs for the latter invited from union members.2 In the end the amount subscribed – £2,300 when the fund was closed in 1957 – was disappointing and, with insufficient funds for the Memorial Hall, some consideration was given to a statue.3 In 1959, when the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), founded by Larkin in 1909, was underplaying his role in the union by making only brief references to him in their golden jubilee publication Fifty Years of Liberty Hall,4 the Workers Union of Ireland (WUI, which became the FWUI in 1978) was seeking to erect a public monument to Larkin in the capital city.

Larkin had established the WUI in 1924 in the aftermath of his expulsion from the ITGWU. In May 1959 the Dublin Trades Union Council submitted a proposal to the Streets Committee requesting use of the site in College Street vacated by the Crampton memorial – a bizarre and ultimately unstable sculpture commemorating a 19th-century surgeon, which had been erected in 1862. The union, while asserting that no justification was required for a Larkin monument, proceeded to defend both their proposal – citing his ‘services as a labour leader, Municipal Councillor, public man, social pioneer [and] outstanding personality’ – and the suitability of the site, noting its proximity to Thomas Ashe Hall, where Larkin worked in the latter years of his life, and to the former police headquarters, where he was first incarcerated.5

Although the union received agreement in principle, nothing came of the proposal at that stage and it was just over ten years, in 1970, before the next application was made. Finally in 1974, the centenary of Larkin’s birth6 and the golden jubilee of the WUI, the corporation granted permission to the union for a monument to be erected on O’Connell Street (Fig 1). President Hillery performed the unveiling ceremony five years later on 15 June 1979 in the presence of members of both the FWUI and the ITGWU, (the two unions merged to become SIPTU in 1990), members of the government and the opposition parties and the Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Kaplin, among many others. A small group of protesters carried placards suggesting that the inner city had not changed since 1913,7 and attention was later drawn to the facility with which Larkin was assigned a space on the main street in the city, when Patrick Pearse was not so recognized.8 Members of Fianna Fáil, who hoped to see a statue of Eamon de Valera joining the pantheon on O’Connell Street, realized that they had lost a valuable site to the Larkin statue.9 A memorial committee was established to oversee the process, thus following a long accepted tradition with regard to the erection of monuments for the public domain. The committee comprised the general president (John Foster) and general secretary (Paddy Cardiff) of the union and eleven other members, including Larkin’s son Denis.10 It fell to the committee to choose a sculptor and, with their union expertise, one might have expected them to have held a competition – limited or open – as was the case with the James Connolly statue in 1993. Instead the commission was offered directly to Oisín Kelly (1915-81). Although a far from democratic procedure, it was in many ways understandable, as Kelly had carried out several substantial public works at this stage and must have appeared to be the most experienced sculptor for such an undertaking. A member of the committee, Bill Attley (later general secretary FWUI and then SIPTU), indicated that it was fellow committee member Donal Nevin who suggested Kelly. Nevin, who was later to become general secretary of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) had published 1913: Jim Larkin and the Dublin Lock-Out in 1964.

The photograph, taken shortly after Larkin returned to Ireland from the US, became an iconic image and by the 1970s there could have been no question of portraying the legendary figure for posterity in any other fashion, as it was this photographic portrait that was used on WUI banners and was commonly seen in the union building

Invited to submit a maquette for the work, Kelly depicted Larkin in the famously hectoring pose – arms outstretched and mouth open wide – as he addressed a crowd. A bronze cast of the maquette – two casts were made at the time – shows that the representation is powerful even on a small scale. Not selected by the sculptor, the pose of Larkin in full flight was captured by photographer James Cashman in Dublin in 1923. The photograph, taken shortly after Larkin returned to Ireland from the US, became an iconic image and by the 1970s there could have been no question of portraying the legendary figure for posterity in any other fashion, as it was this photographic portrait that was used on WUI banners and was commonly seen in the union building. With both the WUI and the Larkin family deeming themselves pleased with the maquette, Kelly proceeded to work on the statue in the backyard of the family home in Firhouse on the outskirts of Dublin.

Following his usual practice, he made several studies of the figure in 2 and 3D and informed himself about his subject before modelling the figure in plaster on a metal armature. Abbey actor Eddie Golden, who was a neighbour, posed for the statue. Once the full-size model in plaster was complete, in 1976, it was cut into sections to be transported to the Dublin Art Foundry, where the year-long casting process – piece-meal rather than lost wax – was carried out by sculptors Leo Higgins and John Behan.11 The over-life size bronze statue was ready for unveiling in 1978. However, a delay ensued as a result of Denis Larkin’s desire that the large pedestal for the statue should be hewn out of a single piece of granite.12 In spite of several attempts at the Ballybrew quarry in Enniskerry, it proved impossible to quarry such a colossal stone and ultimately the pedestal was made out of several blocks. The unveiling prompted a flurry of activity in the Department of the Taoiseach in 1977, when it was discovered that they had not been consulted about President Hillery’s participation in the event. As the opportunity to give due consideration to the matter – ‘in view of the possible controversial and political associations’ – had been denied them, they turned their attention to fine-tuning the President’s speech.

The requirement that appropriate, uncontroversial and unambiguous language be used meant that words like ‘comrades’, present in the early drafts, were omitted from the final text.13 When he was completing work on the statue in 1976 the sculptor, interviewed by John Boland for the Irish Press (8 November), and discussing his career and his ideology, described himself as ‘a bit old-fashioned and literary’. If such attributes as ‘careful preparation’, a concern for ‘technical expertise’ and respect for the patron were considered old-fashioned, then the description was particularly apt.14 Kelly in different discussions throughout his life indicated his interest in the work of Ernst Barlach, whose work he saw on a visit to Frankfurt early in his career; Henry Moore, with whom he studied briefly in London; and the Italian sculptor Marino Marini, whose influence is particularly evident in Kelly’s Chariot of Life in the Irish Life Centre, Dublin. Kelly’s output is more associated with subject pieces than with portrait work, yet he modelled and carved a number of busts – many of family and friends – in his early career, and was commissioned to do a portrait statue of Roger Casement in the late 1960s after Casement’s body was returned to Ireland for reinterment in Glasnevin. The statue, smaller in scale than the Larkin, completed in 1971 and intended for the grave, has had a problematic history and spent many years in OPW storage. The positioning in Glasnevin was eventually thought precarious in the light of the developing Troubles in the North; locating it at the car ferry terminal in D√∫n Laoghaire, which was subsequently proposed and was scarcely appropriate, was not realized and the statue has ended up overlooking the more apposite Banna Strand in County Kerry. The portrait of Casement – more human than heroic – shows him with his hands manacled.

Hands are an important device in Kelly’s work generally, and perhaps nowhere more obviously than in the Larkin statue, where they have immense presence.

Hands are an important device in Kelly’s work generally, and perhaps nowhere more obviously than in the Larkin statue, where they have immense presence. Fergus Kelly remembers his father worrying away at the hands and the difficulties of them being seen from below. Although the sculptor never knew Larkin, he clearly recognized not just that the man had what were described elsewhere as ‘great hands like shovels’,15 but how important they were to the passionate nature of the depiction. After all, this is not a portrait in the strict sense of the word. Recognition of the man is not by way of his handsome features, but is in the expressive manner of his presentation – the energy of his oratory represented not only by way of the gesturing arms but also in the movement of his jacket. The handling of the portrait is unlike any of the other statues on O’Connell Street. Mostly 19th-century works, the statues of Daniel O’Connell, William Smith O’Brien, Sir John Gray, Father Theobald Mathew and – erected in the early 20th century – Charles Stewart Parnell are all passive portrait likenesses by comparison. Charles Baudelaire, writing on the French Salon exhibition in 1859, spoke of the ‘divine nature of sculpture’ being manifest in the ‘motionless figures’, positioned in squares and on streets, that recount the glories of another age. The element of stillness was rejected for Larkin in favour of a dynamic, physical presence revealed as much in the pose as in the roughly textured finish of the bronze. Only John Henry Foley’s statue of Henry Grattan in College Green has a comparable vigour. Larkin was portrayed by several Irish artists in his life-time – notably in drawings and sketches by William Orpen, Seán Keating and Sean O’Sullivan – and by American sculptor Mina Carney, whose bronze bust is in Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane. Carney’s husband Jack was a close friend of Larkin, and she herself served as secretary of the Larkin Defence Committee in 1922 when he was imprisoned in the US. Her robust bronze head, with its worn but determined face, conveys the reality of a portrait taken from life.

Oisín Kelly’s statue, intended to do more than simply reproduce the man, perpetuates the memory of his authoritative leadership When Kelly received the Larkin commission from the WUI he had already carried out a depiction of two workers for the ITGWU. The sculpture was intended for placing outside the new Liberty Hall building in Dublin, where the men (Tom Golden, Eddie’s son, posed for one of the figures) would be seen gazing upwards in awe. But permission to locate the figures was refused by Dublin Corporation, purporting that the sculpture would be a traffic hazard. The Corporation’s intransigence resulted in the two-figure group being offered in 1976 to the union building in Cork, where it is positioned outside County Hall. The Two Working Men and the Casement statue, like the Larkin, were both cast in bronze at the Dublin Art Foundry. Kelly worked closely with the foundry, which, established in 1970, was one of the earliest fine art foundries in the city. The historian FX Martin was among the people who suggested that any Larkin statue should be in bronze because the imperishability of the material would reflect Larkin’s similarly enduring nature.16 Jean Paul Sartre, in his writings on sculpture, addressed the practices of carving (stone) and modelling (bronze) for representing the human body, particularly for public sculptures. He supported the latter practice, dismissing ‘the eternity of stone’ as being ‘a present forever fixed’.17 Yet, Oisín Kelly has ‘fixed’ in bronze that particular ‘present’ of James Larkin, enabling it to be carried forward for and to be revisited by future generations.

Acknowledgements: Many people have been helpful in the course of this research, including several members and former members of SIPTU and members of Oisín Kelly’s family. I would like to thank in particular Francis Devine, Bill Attley, Padraig Yeates, Patricia King, Theresa Moriarty, Jean Kennedy and John Smyth; Fergus and Daniel Kelly; Monica Cullinan, Leo Higgins, Frank Murphy and Ruairi O’Cuiv.

Paula Murphy is a senior lecturer in the School of Art History and Cultural Policy, University College Dublin.

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 30, No 4, 2013