How reliable is historical documentary? Levi Hanes examines Turner Prize Winner Duncan Campbell’s filmic presentation of this question at IMMA this winter

Born in Dublin in 1972 Duncan Campbell completed his BA at the University of Ulster, Belfast in 1996 and his MFA at the Glasgow School of Art in 1998. Now living and working in Glasgow, Campbell has shown in numerous prestigious international institutions and is currently nominated for the 2014 Turner Prize. Drawing on his time spent in Northern Ireland, Campbell produced two films that address the politics and economics of the region. Bernadette (2008) presents a biopic of the controversial republican MP Bernadette Devlin and Make it New John (2009) covers the creation and eventual closure of the DeLorean automobile plant in Dunmurry (creators of the gull-wing door car of Back to the Future, 1985 fame). Campbell’s film Arbeit (2011) extended his focus to the developments of the European project with a personalized biography of German economist Hans Tietmeyer.

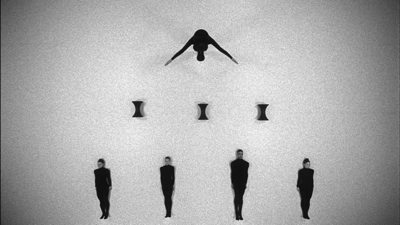

When introduced to the artist Campbell’s films, the viewer is presented with a very different experience from the standard documentary. Rather than establishing the context of the film though standard panoramic location shots or telling signs of the era, the films present us with disorienting effects. Often the films utilize dislocated soundtracks, abstracted shots of the sky or fragments of landscape, close-ups of hands, feet and furniture, and overly long black segments. These are the hallmarks of artist films, but also serve the purpose of disconcerting the viewer and preparing us for a documentary format that sets out to discredit the factual premise of the archival footage it uses. With a palpable interest in the events depicted in the film, Campbell includes the incidental human attributes and attitudes found in the archival footage. Using the outtakes just before and after the film stock traditionally used for broadcasting, he reveals the fabrication of the film production process including the less polished preambles, the clearing of throats, and the off-camera instructions which often contradict the perceived notions of authoritative assurances presented by the protagonist on camera. These off-cuts expose both the protagonist’s and the producer’s manipulation of the media. Campbell extends this reflexive technique in the script, an amalgamation of biographic, autobiographic and artist-created text moving between official documentation, personal recollection, and internalized, diaristic, confessionary stream of consciousness.

Campbell interjects editing breaks and incongruities to remind the viewer that what is presented to them is, in part, a construction

The culmination of these various film processes is a poetic examination of specific key events engendering a locality with far-reaching socio-political implications. Further, Campbell interjects editing breaks and incongruities to remind the viewer that what is presented to them is, in part, a construction. The use of awkward unconnected comments and the subject’s deference to off-camera instructions reveals a vulnerable side to the subject, a protagonist disengaged by the camera nor in command of her environment, and caught unaware by its preambulatory or lingering recording. Moreover, the manipulations of the filmmaker shown on screen by the drawn animations, reminiscent of flecks on dirty film-stock in Bernadette, the filming of studio lights during the narration of Arbeit and the manipulated spoken text throughout the films further highlight and undermine the artifice inherent in linear narrative documentary.

Whether focusing on Northern Ireland or the developments that led to the recent economic crisis in Europe, Campbell takes the personal, the local and international contexts combining them with a melange of film techniques that expose complex geopolitical circumstances surrounding the events and the manipulated construction of narrative authority that most documentary methods seek to hide within a formulaic format. The films present a personal and recognizable circumstance for the viewer while establishing a sense of uncertainty towards the authority and verity of the information provided. Calling on a rich history of film and theatre reminiscent of experiments in filmic representation of memory found in Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), the word/image association films of English experimental filmmaker John Smith and French multimedia artist Chris Marker in addition to the existential absurdity of Samuel Beckett, Campbell synthesizes archival and fabricated film into a method of storytelling that materializes a curious format, neither solely an artistically rendered documentary, nor an essay in the slippery aspects of the indexicality of film documentation. Cambell’s films play out like personal accounts of historic events complicated by emotion, hazy recollections and the often contradicting nature of film evidence.

Duncan Campbell, IMMA, Dublin 7 November – February 2015.

All images ©The Artist.

Levi Hanes is an artist and Irish Research practice-based PhD Scholar at Huston School of Film & Digital Media, NUI Galway.