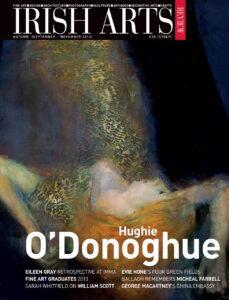

As Irish Design 2015 is launched worldwide, we republish here Jennifer Goff’s assessment of the legacy of internationally acclaimed arch Modernist Eileen Gray

It has taken a long time for the reputation of Irish-born designer Eileen Gray to be accorded the public recognition it deserves but earlier this year earlier the Centre Pompidou in Paris mounted an impressive retrospective of her work, part of which is coming to IMMA in October. Renowned as a designer and a self-taught architect, it is less well known that Gray was also a talented photographer and artist. During her later years she destroyed her personal papers, wanting to be remembered only for her work. From the archives which remain, another fact becomes clear; that despite a lifetime spent in France Eileen Gray remained an Irishwoman at heart.

Born in Enniscorthy, Co Wexford, Gray described Ireland as ‘home.’1 She trained as a painter at the Slade School in London. Along with several friends including Wyndham Lewis, Kathleen Bruce, Jessie Gavin, and Gerard Kelly, Gray settled in Paris in 1902, where she attended the √âcole Colorossi and then the Académie Julian. She ‘arrived as an Irish immigrant to Paris in 1902. She didn’t really intend to stay there forever, but somehow things worked out that way. It was very different to home in Wexford.’2 In 1901 – 1902 Gray met Paul Henry, introduced by a lifelong friend, Stephen Haweis, who studied with Gray at the Académie Julian. In company with her friends Gray spent evenings at the Café de Versailles and the Chat Blanc on the rue d’Odessa where Roderic O’Conor was also documented as being in attendance. Gray was establishing herself as an artist at the time and was pleased to have a painting accepted at the 120th Salon des Artistes Fran√ßais.3 Her library was filled with art books including Apollinaire’s Les Peintres Cubistes (1913), Neo Plasticisme (1920) by Piet Mondrian, Picasso’s Guernica (1938), André Breton’s The Surrealist Manifesto Au Grand Jour (1927), and a catalogue from a Futurist exhibition held in Paris in February 1912. From the 1930s to the 1960s she produced a series of gouaches, collages and monotypes inspired by Futurism and Vorticism. She experimented with artistic photographs and also produced several African-inspired sculptural heads.

Gray settled permanently in Paris in 1906, at 21 rue Bonaparte. Here she continued in her studies of lacquer (begun in London) with Seizo Sugawara. Perfecting her skills, she established a workshop at 11, rue Guénégaud in 1910 which lasted for more than twenty years.4 Gray produced and exhibited innovative lacquer work ranging from screens, chairs, tables, bureaux, beds, and dressing tables. Her work achieved critical acclaim in the media and attracted clients such as fashion designer Jacques Doucet and society hostess Madame Mathieu Lévy. Inspired by the Deutscher Werkbund, Gray produced domestic lacquer ware; bowls, plates and toiletries, some of which she hoped to create for a moderate household budget. These pieces evoke the artistic movements which shaped Gray’s early career; vorticism, Cubism, and Futurism. In 1917 Vogue reported on Eileen Gray’s work, illustrating several screens and an unfinished door panel, commissioned by Doucet. The story depicted on the panel is the Irish myth of the Children of Lir. Gray was very interested in Irish mythology, owning several books on the subject.

Gray quickly established herself as a designer when she opened her shop Jean Désert in 1922. Her textiles and carpets elicited much enthusiasm from her clientele. The carpets were produced at an atelier at the rue de Visconti, set up with Evelyn Wyld, in 1909. They learned weaving and natural wool dyeing techniques from Arab women in North Africa.5 The wool that they used came from Auvergne and was dyed in Paris. From the 1920s to the 1930s Gray refined their method, using a hand-knotting technique that precluded machine production, resulting in the first textured carpets. Many templates were executed in gouache or collage. Earlier rugs illustrate identifiable geometric forms in a range of colours and many designs are formal exercises in abstract art. Some rugs were given names such as ‘Ulysses,’6 in homage to the Irish writer James Joyce, whom she knew. Others were named after places she visited such as Roquebrune, Saint Tropez and Castellar (Fig 6). However, several rugs had Irish themes – notably ‘Kilkenny’7 and ‘Wexford.’

Her use of media was novel, combining as she did lacquer, chrome, celluloid, plastics, perforated metal and cork in revolutionary fashion

After the war Gray hoped to mass-produce her lacquer work, but the expense of the process proved prohibitive. She excelled as the interior designer of the rue de Lota apartment, 1918-1924, for Madame Mathieu Lévy, creating an architectonic environment with unique furnishings. In 1923, Gray exhibited the ‘Bedroom boudoir for Monte-Carlo’ a dual-purpose, multi-functional living room space. Though criticized by French critics, the room was praised by members of the De Stijl. Architect J J P Oud wrote to her in Ireland requesting copies of reviews of her work, and in referring to her native Ireland he inquired ‘Do you have any modern movement in your country?’8

From the mid 1920s to the end of her life she consistently tested herself a designer. Her use of media was novel, combining as she did lacquer, chrome, celluloid, plastics, perforated metal and cork in revolutionary fashion. Furniture produced for her domestic architectural projects illustrate how Gray became engrossed in the processes of living. Her furniture designs for Roquebrune (E1027) focused on compactness, versatility and practicality. Some pieces were integrated into the architecture; others were free standing serving multiple functions. The adjustable table, an iconic piece, had a vertical extension to adjust its height. Her dining chairs, faultless in proportion, were designed to aid digestion. The Bibendum chair, in homage to the Michelin man, reflected her wit (Fig 3). The slender rectangular bathroom cabinet with its asymmetrical doors opens to reveal cork- fronted swivel drawers, glass shelves and a full-length mirror (Fig 4). The Transat chair (Fig 9) made of wood and metal, shows how she succinctly observed the user of the chair, adjusting its length, size and headrest accordingly in the design. In the furniture produced for her own house ‘Tempe à Pailla’, Gray displays her mastery in understanding context and setting. Some pieces display abstracted architectural plans of the house, such as an amoeba-shaped occasional table (Fig 7). Furniture was designed to be easily stored, such as the S bend chair, which folds in on itself.

As a self-taught architect she had begun to experiment directly with architectural forms from 1923. Her six-year collaboration with Jean Badovici and acquaintance with Le Corbusier provided her with the final impetus for an independent career. Gray’s archives contain over one hundred sketches, drawings, plans, elevations, descriptions and notes. Some projects were realized while others were left unresolved. One of her hypothetical projects looked to her Irish heritage. ‘The Irish Epic,’ 1946-47, was directly inspired by a publication by George Dottin in the 1920s which describes at length the various Irish myths and legends of C√∫chulainn, amongst others. She had explored several amphitheatre projects, from her early set designs completed for ‘Ballet des Animaux’ culminating with the ‘Cultural and Social Centre.’ A photograph remains of the model of the stage set, with rocks and trees. Following an exhibition of her carpets at Bank of Ireland Headquarters in May/June of 1973, Gray corresponded with Dorothy Walker, (see Irish Arts Review 1999, pp. 118-125) stating that she always wanted to have a carpet made in Ireland.9 She yearned to return home, stating ‘I long for Ireland’10 and writing ‘anything to do with Ireland always moves me.’11 Donegal carpets finally realized her dream when a series of rugs, many with Irish themes was produced in 1975 (Fig 6).

In 1922 Mainie Jellet and Evie Hone met Gray through a mutual friend Kate Weatherby. Gray had the most impact on Mainie Jellett, as she encouraged Jellet to produce her own rug designs.12 In 1927 Jellett designed and had rugs made at the Gray Wyld workshop in rue de Visconti. Though some of Jellett’s carpets are formal exercises in Albert Gleizes’s theories of abstract cubism – other clearly demonstrate Gray’s influence. A circular rug design of 1933 is directly inspired by Gray’s rug Tapis Ronde which she created for the living room of E1027.13 Gray’s achievements in architecture were recognized with an honorary fellowship bestowed by the RIAI of which she was exceedingly proud. Too frail to travel to Ireland to attend the ceremony, the Irish Ambassador to France, Edward Kennedy presented her with the award.14

On 22 July 1975 in a letter to the National Museum of Ireland Eileen Gray wrote, ‘I should have liked so much to have something permanent in Ireland but I suppose it is too late now.’ Gray died in 1976, while still working on models for new screens. In May 2000 the National Museum of Ireland purchased the contents from Gray’s apartment and personal ephemera. The Eileen Gray collection and permanant exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland was made possible through the efforts of Dr Patrick F Wallace and the Minister of the Arts Heritage, Gaeltacht and the Islands, Síle de Valera. This exhibition at IMMA pays tribute to Gray’s career as a leading member of the modern movement while celebrating her Irish roots. It will feature a number of previously unseen works offering new insights into Gray’s extraordinary career. In 1968 when architectural critic Joseph Rywkert published his feature in Domus enlightening the world once again to her architecture, Eileen Gray wrote in a letter to her niece ‘You did tell him that I was born in Ireland, didn’t you, for the old few figures that remain, I was known as Irish, which I much preferred.’15

Jennifer Goff is Curator of Furniture, Music, Science & the Eileen Gray Collection at the National Museum of Ireland.

1 Binchy, Maeve, The Irish Times, 16 February 1976

2 as note 1.

3 Pitiot, Cloe, ‘Eileen Gray, la poésie de l’enigme,’ Eileen Gray, Editions de Centre Pompidou Paris, 2013, p.5.

4 Starr, Ruth, ‘Eileen Gray: a child of Japonisme?’ Artefact, Issue one/Autumn 2007.

5 V& A Archive AAD/9/4-1980.

6 V & A Archive AAD 9/2/1980 client list book.

7 National Museum of Ireland NMIDF2000.110.

8 V& A Archive J.J.P.Oud postcard to Eileen Gray 31 August 1924 AAD/1980/9.

9 NCAD Library Gray, Eileen, in correspondence with Dorothy Walker 17 September 1973. 22 November 1973.

10 NCAD Library Gray, Eileen in correspondence with Dorothy Walker 12 August 1973.

11 NCAD Library Gray, Eileen in correspondence with Dorothy Walker 15 June 1973.

12 Arnold, Bruce, Mainie Jellett and the Modern Movement in Ireland, Yale University Press, London, 1991, p.67.

13 National Museum of Ireland Collection. NMIEG:2003.110-114 Circular Rug Gouaches

14 Letter written to Robin Walker from the President of the RIAI, Kevin Fox.

15 National Museum of Ireland NMIEG 2003.298.

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 30, No 3, 2013